This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

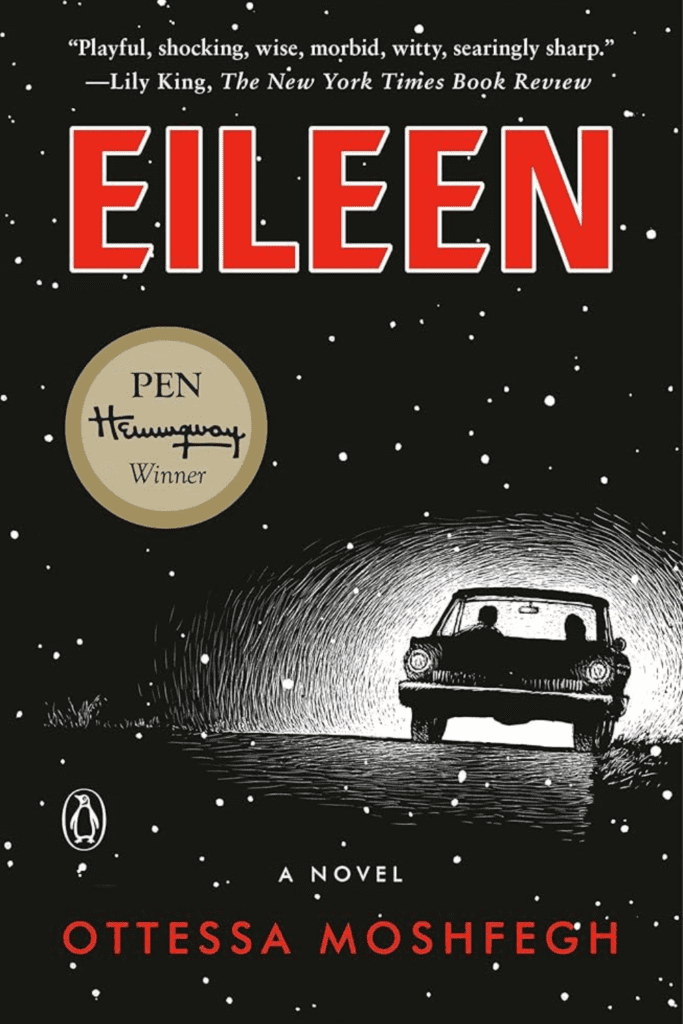

“Eileen” is a mystery-thriller crime book following our main character’s disappearance during the week leading up to Christmas.

- Date finished: March 2nd, 2024

- Pages: 260

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Novel

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Mystery | Literary Fiction | Thriller

Buy “Eileen”

“Eileen” is set during the week leading up to Christmas, this dark, thrilling, moody story follows the disappearance of 24-year-old Eileen.

“Eileen” is the second Ottessa Moshfegh book I’ve read (and within the same year) and it did not disappoint. Previously, I had read “My Year of Rest and Relaxation.” You can read that review here.

Working at a juvenile detention center, 24-year-old Eileen lives a less-than-ideal life. Essentially, she’s stuck in X-ville with an alcoholic misbehaving father—their relationship is fraught, codependent, and emotionally abusive.

Eileen is self-critical, insecure, and very angry:

But I deplored silence. I deplored stillness. I hated almost every-thing. I was very unhappy and angry all the time. I tried to control myself, and that only made me more awkward, unhappier, and angrier. I was like Joan of Arc, or Hamlet, but born into the wrong life—the life of a nobody, a waif, invisible. There’s no better way to say it: I was not myself back then. I was someone else. I was Eileen. (p. 2)

I was dark, you might say. Moony. But I don’t think I was really so hardhearted by nature. Had I been born into a different family, I might have grown up to act and feel perfectly normal. (p. 8)

Eileen is depraved in all senses of the word and this narrative is her retrospective to her disappearance:

So here we are. My name was Eileen Dunlop. Now you know me. I was twenty-four years old and had a job that paid fifty-seven dollars a week as a kind of secretary at a private juvenile correctional facility for teenage boys. I think of it now as what it really was for all intents and purposes—a prison for children. I will call it Moorehead. Delvin Moorehead was a terrible landlord I had years later, and so to use his name for such a place feels appropriate.

In a week, I would run away from home and never go back.

This is the story of how I disappeared. (p. 12)

We come to understand, that due to her stifling upbringing, Eileen is unable to form good long-lasting relationships and much less a good life for herself. She’s desperate for an out and instead, she loses herself in romantic obsessions: first with Randy, and then the elusive Rebecca, the new, older, and only female psychotherapist that is introduced to the Moorehead Junevile’s detention center.

As for Rebecca, we could argue that she might not quite be real. She might just as well be a figment of Eileen’s imagination — there to help her gain the courage to leave her father and miserable life behind for good.

Eileen is longing for an escape… and by any means possible. Naturally, she even considers suicide. Most people do when they consider killing their old selves and escaping from their miserable life.

My curiosity for the stars is obvious: I wanted something to tell me my future was bright. I can imagine myself saying at the time that life itself was like a book borrowed from the library—something that did not belong to me and was due to expire.

How silly. (p. 71)

In a way, it’s Eileen’s toxic codependent relationship with her father that keeps her grounded in X-ville. Even in her deepest, darkest thoughts, his presence and judgment remain at the back of her mind:

As I parked the car outside the cinema and rolled up the windows, it struck me again how easy it would be to die. One snagged vein, one late night skid on the icy interstate, one hop off the X-ville bridge. I could just walk into the Atlantic Ocean if I wanted to. People died all the time. Why couldn’t I?

“You’ll go to hell,” I imagined my father would say, busting in on me as I slit my wrists. I was afraid of that. I didn’t believe in heaven, but I did believe in hell. And I didn’t really want to die. I didn’t always want to live, but I wasn’t going to kill myself. And anyway, there were other options. I could run away as soon as I had the courage, I told myself. The dream of New York City beckoned like the twinkling lights of the cinema marquee—a promise of darkness and distraction, temporary and at a cost, but anything was better than sitting around. (pp. 55-56)

Eileen’s relationship with her father and her resulting lack of self-esteem, reminds me a lot of Lydia’s relationship with her mother in “Woman, Eating.” You can read my review of the book here.

And if I bought a stick of butter, he would hold it between his fingers and say, “I can’t eat a stick of butter for dinner, Eileen. Be reasonable. Be smart for once.” When I walked through the front door, his response was always, “You’re late,” or “You’re home early,” or “You’ve got to go out again, we’re in short supply.” Although I wished him dead, I did not want him to die. I wanted him to change, be good to me, apologize for the half decade of grief he’d given me. And also, it pained me to imagine the inevitable pomp and sentimentality of his funeral. The trembling chins and folded flag, all that nonsense. (p. 64)

Without her mother and her older sister around, Eileen becomes the emotional caretaker of her alcoholic and emotionally abusive father. Like most children of codependent parents, she becomes a surrogate partner and mother to her parental figure, as Eileen notes in this passage:

Nothing fit me right, as I’ve said, so I often wore layers of sweaters or long underwear just to fill things out. Lying there, I had a bad habit of drumming my fists on my stomach and pinching the negligible amount of fat on my thighs. I sincerely believed that if there were less of me, I would have fewer problems. Perhaps it was for this reason that I wore my mother’s clothes—to be vigilant in my mission never to reach even her minor proportions. As I’ve said, her life, the life of a woman, seemed utterly detestable to me. There was nothing I wanted less back then than to be somebody’s mother, somebody’s wife. Of course, I’d already become just that for my father by the tender age of twenty-four. (p. 185)

Towards the end of the novel, the death (i.e., murder) of Rita Polk becomes symbolic of her severing ties with her old self, her toxic relationship with her father, and her job at the Juvenile Detention Center. We also suspect that many of the young boys might be more similar to Eileen and Leonard (Rita Polk’s son) than we first come to understand. Most of these children are victims of childhood neglect, abuse, and so forth.

The ending, sordid as it was, made for a satisfying read — no, gratifying read.

Though I didn’t drink coffee—it made me dizzy—I walked to the corner where the coffee pot was because there was a mirror on the wall above it. Looking at my reflection really did soothe me, though I hated my face with a passion. Such is the life of the self-obsessed. The time I languished in the agony of not being beautiful was more than I care to admit even now. (p. 15)

Memories, ghosts, dread can be like that, in my experience—they can come and go at their own convenience. (p. 45)

One day I’d run off, I knew. Until then, I would pine. (p. 61)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply