This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

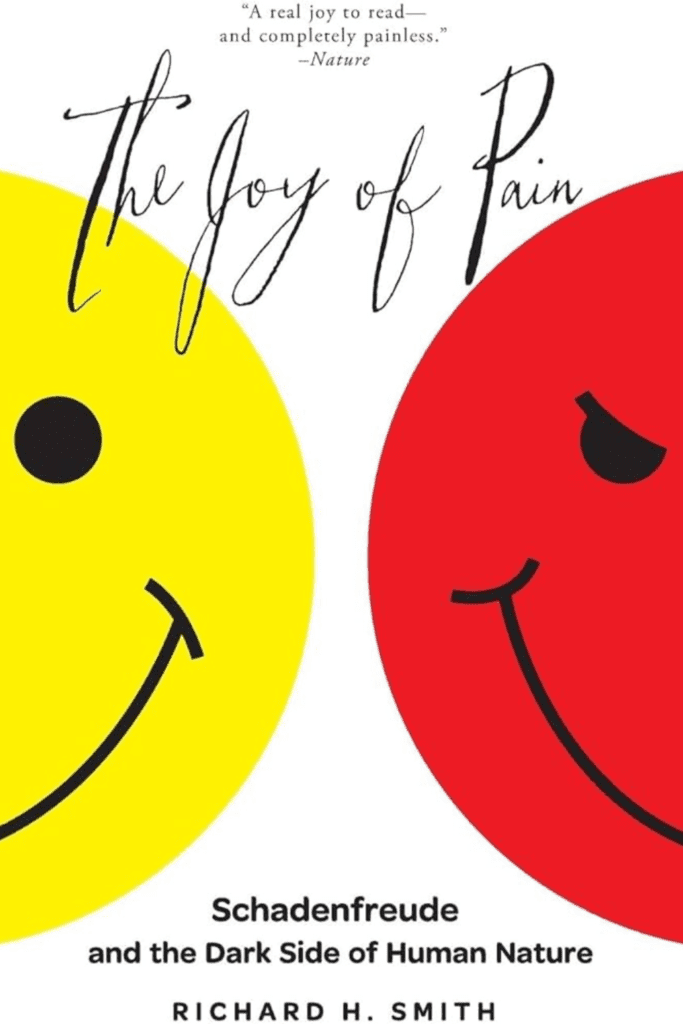

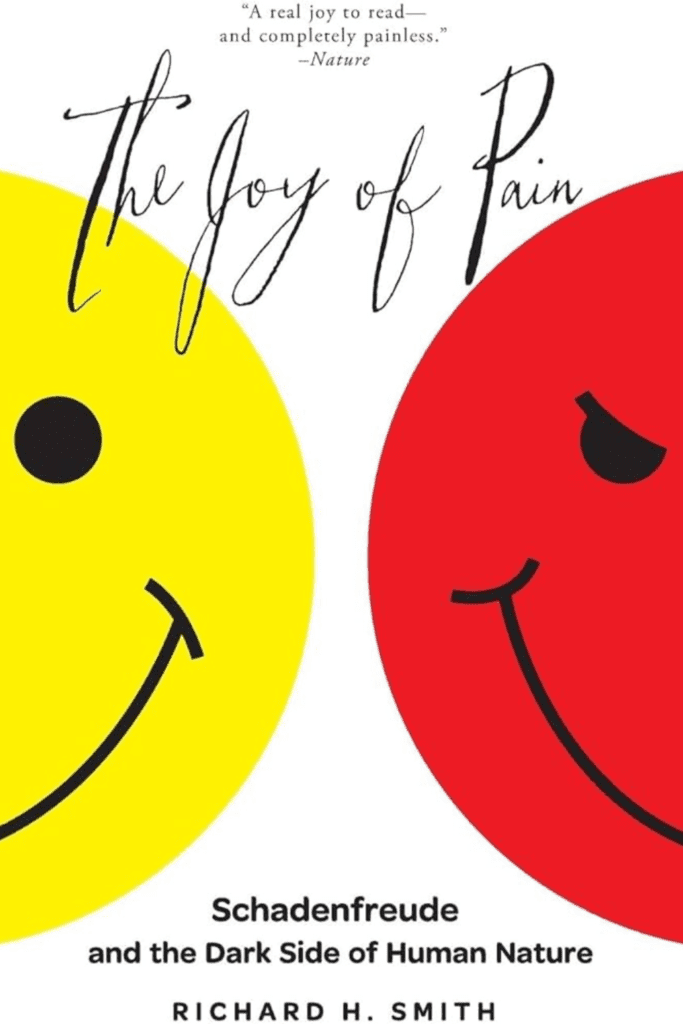

“The Joy of Pain” is a non-fiction book that explores both the psychological and sociological nature of schadenfreude — that shameful joy we experience when we watch the misfortunes of others (those we are jealous of, enemies, and even sometimes towards our friends, family, and acquaintances.)

- Date finished: April 1st, 2024

- Pages: 238

- Format: Hardback

- Form: Non-Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Non-Fiction | Psychology | Sociology

As I mentioned, “The Joy of Pain” is an exploration of the “dark side of human nature” (labeled Schadenfreude by the Germans) as titled by the author Richard H. Smith.

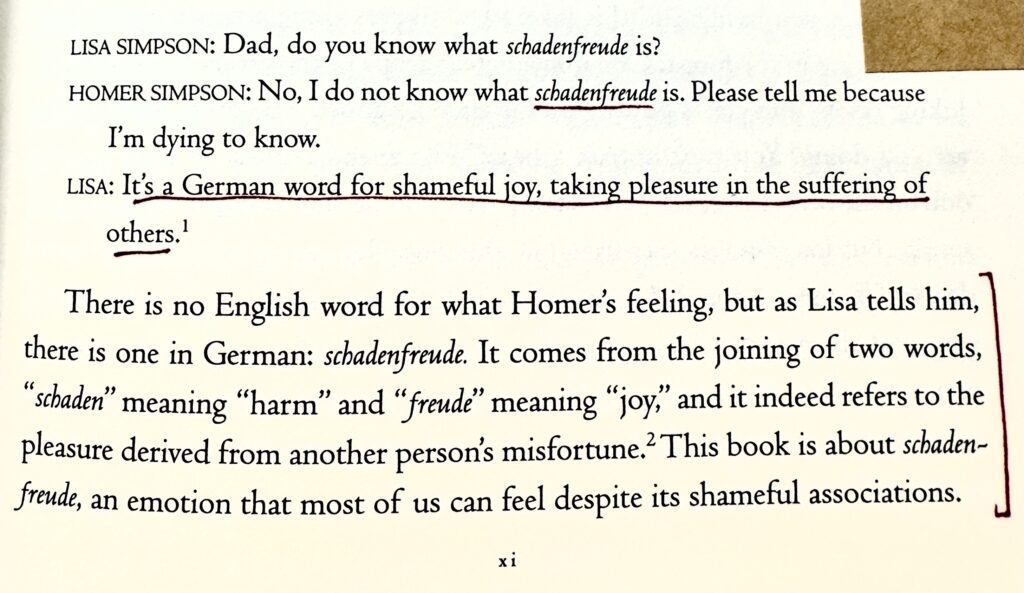

First things first, what is Schadenfreude?

I thought I’d enjoy this “The Joy of Pain” more. As in, I’ve learned a lot but I thought I’d pull more from it. It had been sitting on my shelf for years, tempting me to pick it up.

Through examples from The Simpsons to Hitler to Abel and Cain’s story to the hit TV show ‘To Catch a Predator,’ the author captures, through a sociological lens, the many faces of schadenfreude, that shameful yet self-indulgent joy at someone else’s pain and misfortune.

Here are a few things that I’ve learned and enjoyed reading about:

Learning about our relation to schadenfreude regarding our feelings of envy and jealousy, and our moral and societal conditioning when it comes to justice and therefore the deservingness of misfortunes.

This book had me thinking about how we are more prone to encounter schadenfreude daily towards people online and the proliferation of influencers, content creators, and celebrities.

We have always enjoyed public shame. That is why we tuned into American Idol for so long. Now, we have a large scope of reality TV shows whose whole appeal is to embarrass and villainize their contestants (I’m looking at you Love Island USA 2024.)

We are more likely to engage in schadenfreude when our self-esteem is threatened and when our weaknesses are exposed and mirrored back to us:

“Psychologist Tom Wills has outlined a theory that explains why comparisons with those less fortunate can enhance a person’s subjective sense of well-being. Normally, we feel uncomfortable observing someone’s suffering. However, Wills argues that our preferences change when we have suffered, our self-esteem has taken a hit, or we are chronically low in self-esteem. Under these conditions, comparing with someone just as unfortunate or—even better—with someone who is less fortunate has restorative power. Opportunities for downward comparisons can be passive or active. In the former case, we might seek out opportunities that naturally occur all around us, such as stories in the tabloid press or gossip among friends and acquaintances. In the latter case, we actively derogate others or deliberately cause harm to someone, thus creating downward comparison opportunities.” (p. 25)

Then, there’s a whole section talking about how schadenfreude provokes humor, and laughter even, because it is deeply entrenched in our superiority complex. (p. 27)

“Is it any surprise that hyperbole such as, “Tragedy is when I cut my finger. Comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die,” made by comedian Mel Brooks, can seem more than simply eccentric?” (p. 29)

Our grapple with developing self-esteem and a healthy bout of narcissism originates from our youth, which we often label ‘sibling rivalry’:

“Most people have seen similar displays in kids. his may be one reason why cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker characterized childhood in this way:

In childhood we see the struggle for self-esteem at its least disguised. The child is unashamed about what he needs and wants most. His whole organism shouts the claims of his natural narcissism…. We like to speak casually about “sibling rivalry,” as though it were some kind of byproduct of growing up, a bit of competitiveness and selfishness of children who have been spoiled, who haven’t yet grown into a generous social nature. But it is too all-absorbing and relentless to be an aberration, it expresses the heart of the creature: the desire to stand out, to be the one in creation. When you combine natural narcissism with the basic need for self-esteem, you create a creature who had to feel himself an object of primary value: first in the universe, representing in himself all of life.” (p. 60)

Our self-interested motives come to a halt when exposed in society (p. 64) and so is our capacity for revenge, or wanting to right a wrong (p. 87) that has been done to us:

“Baumeister and Bushman note that many of the rules that we learn, such as turn-taking and respect for the property of others, are based on moral principles that inhibit self-interested behavior. Especially when we are among people we know well, moral emotions such as guilt and shame help in this process. We feel guilty if we satisfy only our own needs and disregard the interests of those in our own group or family, and we feel ashamed when our selfish actions are made public. But our self-interested concerns surface easily. It often requires deliberate, planful efforts on our part to act in culturally appropriate ways.

Baumeister and Bushman put it nicely:

Generally, nature says go, culture says stop….The self is filled with selfish impulses and with the means to restrain them, and many inner conflicts come down to that basic antagonism. That conflict, between selfish impulses and self-control, is probably the most basic conflict in the human psyche.” (p. 62)

Concerning the notion of revenge, schadenfreude can feel and be necessary, since “revenge” becomes a way to “restore self-esteem.” (p. 90)

“Evolutionary psychologists conclude that vengeful urges are instinctual.

Acting vengefully in response to harm would have served as a powerful, adaptive deterrence against future harm. Legal scholars like Jeffrie Murphy agree.

Murphy suggests in his book, Getting Even: Forgiveness and its Limits, that vengeful feelings and the actions that they inspire should have helped our ancestors defend both themselves and the moral order.& He argues that a moral person must have both an intellectual and emotional reaction to a wrong. It is probably the emotional commitment to insisting on one’s rights that leads to corrective action. If we feel no outrage over injustice, we will fail to redress a wrong.” (p. 87)

However, we think of revenge to be more fulfilling than it actually is. The author explains that revenge has its limitations due to our tendencies to ruminate, which brings our focus and attention back to the original offense:

“Thus, it appears that people often overestimate how satisfying revenge will be because they are unaware that their vengeful actions can cause them “to continue to think about (rather than forget) those whom they have punished.” And so, does revenge work? Because of rumination, there may be at least one downside. If we go by these researchers’ results, after people have taken revenge, rumination may cause increased regret over their vengeful behavior.” (p. 90)

So how can we enjoy and benefit from our revenge?

Much like when we watch our heroes on screen, we want them to right the wrong while maintaining the “moral high ground.” Therefore, the author explains that it is more rewarding when an individual bares witness instead when it comes to the misfortunes of their perpetrator (i.e., the enemy):

“The strong impress of cultural norms against revenge means that indirect revenge, the act of bearing witness, might in fact bring greater pleasure to an individual than direct revenge. There is a lot to be said, in terms of psychological gain, for this indirect, “passive” form of out-come. Although one might temper the outward expression of joy, there is no danger of being browbeaten over having acted in an uncivilized way. At the same time, the misfortune should go a long way toward appeasing vengeful feelings.

The experiment by Carlsmith and his colleagues partially supports this idea as well. In an additional condition, participants witnessed the punishment rather than enacting it. This produced significantly greater positive feelings than the “punisher” condition, comparable to another “forecaster” condition in which participants predicted reactions to witnessing the punishment. Participants in the “witness” condition also ruminated less. Yes, witnessing the suffering of someone who has wronged us has a lot going for it over inflicting the suffering ourselves. It is schadenfreude, guilt-free (and avoids counter revenge too!)” (p. 91)

And finally, the last aspect that caught my attention is the huge roles envy and jealousy play in our feelings of schadenfreude. To explain this, the author takes Abel and Cain’s story as the primary example:

Satan, although powerful in his own right, is overloaded with envy of Jesus, who has God’s greater favor. Weakened by this, his pride wounded and his malice aroused, he plots revenge and releases evil into the world. Is there a more alarming vision of what envy, unleashed, can do? It is hard to read this and think about envy in a benign, cheerful way.

Christian traditions also include envy in the cast of the deadly sins.

Although the pain of envy is its own kind of punishment, the consequences of the sin of envy are singularly unpleasant. In Dante’s vision of Purgatory, the envious have their eyes sewn shut with wire. This seems fitting, for the root of the word envy derives from in- “upon” + videre “to see.” 4 People feeling envy look at advantaged others with malice, casting an “evil eye” upon them—and look with pleasure when misfortune strikes. Envy may also be a sin that catalyzes others. Christian philosopher George Aquaro makes the case for envy being the core emotion driving most sinful behaviors, the one that creates the necessity for other commandments. Without envy, Cain may not have murdered Abel.

Alas, because the commandment to avoid envy may be impossible to follow, we must also have “thou shalt not kill.” (p. 128)

And then the author presents the great paradox of envy – it is destructive rather than constructive:

Envy can imprison us in a paradox because we feel both a sense of injustice and a sense of shame. In Heider’s words, “Envy is fraught with conflict, conflict over the fact that these feelings should not be entertained though at the same time one may have just cause for them.” Envy, by this logic, is a hostile feeling that seems justified and yet damnable. It comes with an aggressive urge having a subjectively righteous character, and yet, acting on this hostility in a way that reveals one’s envy is a repugnant move. (p. 131)

For those who don’t struggle with such morals, envy can drive them to extreme horrors – the deepest form of schadenfreude, the Darkest Side of Human Nature. Tyrannical figures like Hitler come to mind:

“Decades later, when Albert Speer, Hitler’s top architect, was asked why Hider was anti-Semitic, he gave three reasons. One was Hitler’s pathological desire to destroy. Another was that he blamed the Jews for Germany’s defeat in World War I, thus denying him the opportunity to achieve his dream of becoming an architect. But a third reason, probably related to his frustrated dreams as well as to a desire to destroy, was that he “secretly admired and envied the Jews.”” (p. 146)

“As the 17th-century writer François de la Rochefoucauld expressed in a maxim, “If we had no faults of our own, we would not take so much pleasure in noticing those of others.”” (p. 9)

“Because self-interest so often drives our emotional reactions to events, even when these events also entail a misfortune for others, we can feel pleased if we gain from the misfortune.” (p. 59)

⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply