This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

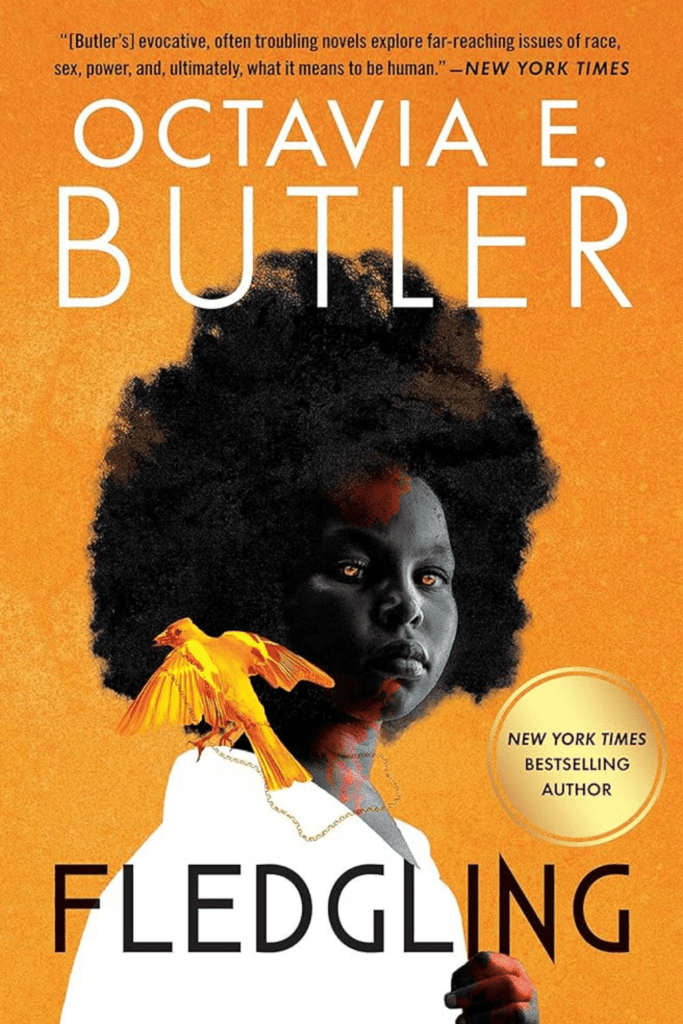

“Fledgling“ follows a genetically modified, seemingly young-looking, vampire who’s lost her memory. She’s tasked with saving herself and the ones she loves from those who caused her harm and murdered her family.

- Date finished: January 15th, 2025

- Pages: 320

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Fiction | Vampires | Science Fiction

Buy “Fledgling“

“Fledgling“ is a story about discovery, agency, sexuality, race, and family through the newly reborn, genetically modified, amnesiac, child-looking vampire named Shori.

“Fledgling“ is one of the most original vampire books I’ve ever read. I’ve been on a real vampire kick in the last two years while drafting my own.

From the start, I was immediately rooting for Shori. She’s considerate and inquisitive, and she shoulders the heavy responsibility to uncover what happened to her, her family, and her memory while connecting and creating bonds with strangers of both kinds – Ina (vampires) and Symbiont (humans).

I particularly enjoyed the beginning in which she researched common tales & myths about vampires:

Wright told me what he remembered about vampires—that they’re immortal unless someone stabs them in the heart with a wooden stake, and yet even without being stabbed they’re dead, or undead. Whatever that means. They drink blood, they have no reflection in mirrors, they can become bats or wolves, they turn other people into vampires either by drinking their blood or by making the convert drink the vampire’s blood. This last detail seemed to depend on which story you were reading or which movie you were watching. That was the other thing about vampires. They were fictional beings. Folklore. There were no vampires. (pp. 15-16)

Shori’s identity as an Ina vampire brings about a host of questions, inequalities, and transgressions. We understand that she’s a feared vampire due to her dark skin. Dark skin, in this context, is a result of genetic experimentation to resist sunburns and be able to walk in daylight, which also gave Shori a strong scent and venom, making her more powerful than the other Ina males and females.

“After a while, Wright asked, “Why did you think she had a better chance of surviving?”“Her dark skin,” Iosif said. “The sun wouldn’t disable her at once. She’s a faster runner than most of us, in spite of her small size. And she would have come awake faster when everything started. She’s a light sleeper, compared to most of us, and she doesn’t absolutely have to sleep during the day.”“She said she thought she was an experiment of some kind,” Wright said.“Yes. Some of us have tried for centuries to find ways to be less vulnerable during the day. Shori is our latest and most successful effort in that direction. She’s also, through genetic engineering, part human. We were experimenting with genetic engineering well before humanity learned to do it—before they even learned that it was possible.”“We, who?” I asked. “Our kind. We are Ina. We are probably responsible for much of the world’s vampire mythology, but among ourselves, we are Ina.” (p. 66)

However, at the start of the book, all of this is not yet known about her. Instead, she’s infantilized by her size, race, memory loss, family loss, and openness to trust those around her. Her encounter turned relationship with Wright highlights this as he calls her ‘jailbait’ (p. 12), mind you, before sleeping with her.

“How old is she?” “I thought she was maybe ten or eleven when I met her. Later, I knew she had to be older, even though she didn’t look it. Maybe eighteen or nineteen?”Iosif smiled without humor. “That would make things legal at least.” Wright’s face went red, and I looked from him to Iosif, not understanding. “Don’t worry, Wright,” Iosif said after a moment. “In fact, Shori is a child. She has at least one more important growth stage to go through before she’s old enough to bear children. Her child-bearing years will begin when she’s about seventy. In all, she should live about five hundred years. Right now, she’s fifty-three.” (p. 64)

Wright is an insightful choice of character. He’s a white male in his early twenties encountering this new world with his preconceived judgments and white savior complex. Although he’s not racist, he still represents humans’ propensity to be sexist and biphobic as he slut-shames anything that goes against his heteronormative ideals. Eventually, he does accept and understand the Ina way and concedes to his part in Shori’s life as her Symbiont. In the end, he becomes a better supportive character valuing mutualistic symbiosis. He doesn’t lose agency, instead, he becomes interdependent and is changed for the better.

“Did you sleep with any of them?” “Did I have sex with them, you mean? No. Except for the one woman, I fed and came back to you. I stayed longer with her because something in her comforts and pleases me. Her name is Theodora Harden. I don’t know why I like her so much, but I do.”“Swing both ways, do you?” I frowned, startled and confused by the terrible bitterness in his voice. “What?” “Sex with men and with women?” “With my symbionts if both they and I want it. For the moment, that’s you.” “For the moment.” (pp. 84-85)

The novel also explores the question of consent as the humans (Symbiont) are said to enjoy being bitten, almost as if it is sexually rewarding to them. Shori, however, is committed to doing the right thing, that is to ensure those she makes her Symbionts want to be with her of their own will. I believe that her amnesia aids in questioning the Ina ways, even the habits that are ascribed as ethical and normal. It is through her journey of discovery that she regains her agency and defends others like her Symbiont, the late Theodora.

“I remember,” he said. He sounded angry. “But I didn’t know then that I was agreeing to be part of a harem. You left that little bit out.” I knew what a harem was. One of the books I’d read had referred to Dracula’s three wives as his harem, and I’d looked the word up. “You’re not part of a harem,” I said. “You and I have a symbiotic relationship, and it’s a relationship that I want and need. But didn’t you see all those children? I’ll have mates someday, and you can have yours. You can have a family if you want one.” He turned to glare at me, and the car swerved, forcing him to pay attention to his driving. “What am I supposed to do? Help produce the next generation of symbionts?” I kept quiet for a moment, wondering at the rage in his voice. “What would be the point of that?” I asked finally. “Just as easy to snatch them off the street, eh?” I sighed and rubbed my forehead. “Iosif said the children of some symbionts stay in the hope of finding an Ina child to bond with. Others choose to make lives for themselves outside.” (pp. 83-84)

This Ina society is interdependent, free, caring, sexually liberated, community-focused, and loyal to their families and clans. In actuality, they defy anything we know to believe and fear from vampires.

“We went through a door at the end of the hallway and out onto a broad lawn. I stopped in the middle of the lawn. “Do they mind?” I asked. “Mind?” “That you need eight. That none of them can be your only one.” I paused. “Because I think Wright is going to mind.” “When he understands that you have to have others?” “Yes.” “He’ll mind. I can see that he’s very possessive of you—and very protective.” He paused, then said, “Let him mind, Shori. Talk to him. Help him. Reassure him. Stop violence. But let him feel what he feels and settle his feelings his own way.” “All right.” “I suspect this kind of thing needs to be said more to my sons than to you, but you should hear it, at least once: treat your people well, Shori. Let them see that you trust them and let them solve their own problems, make their own decisions. Do that and they will willingly commit their lives to you. Bully them, control them out of fear or malice or just for your own convenience, and after a while, you’ll have to spend all your time thinking for them, controlling them, and stifling their resentment. Do you understand?” (pp. 72-73)

Furthermore, the Ina operate in a symbiotic relationship with their Symbionts—they can extend human lives up to 200 years. Still, these humans need their Ina, and the Ina need their human Symbionts to survive. In a way, it’s a reciprocal relationship and a more ‘ethical’ way for the undead to exist and consume blood.

However, it is Shori’s hybridity, a mix of Ina and human DNA, that truly allows for a healthier mutualistic symbiosis. One that overcomes the Silk family’s speciesism, much reminiscent of humans’ white supremacy.

This is further highlighted in The Council of Judgement, which is quite dissimilar (in a good way) from human law as the Ina can detect truth from lies, and they therefore value that truth above representation and bribes (pp. 220-221.) In this council, Milo Silk reveals his racism (shown here as speciesism as well) openly to Shori:

“You’re not Ina!” he shouted. He slammed his palm down on the table, making a sound like a gunshot. “You’re not! And you have no more business at this Council than would a clever dog!” (p. 238)

Luckily, Shori’s amnesia proves her newfound agency and great morality to protect, in equal measures, both Ina and Symbionts. She is the physical representation of their bright future, one that challenges and overcomes the Silk family’s rigid, murderous superiority. One in which Ina and Symbionts are truly mutualistic.

Overall, this book encompasses a lot and does so masterfully. It is a bildungsroman, murder mystery, vampire retelling, and court drama all wrapped in one tale. I loved this book and Shori is a new all-time favourite character. This was my first time reading an Octavia E. Butler book and it saddens me to learn that this was her last novel. I will miss Shori and imagine myself a bright future for her.

For now, I will be reading Butler’s Earthseed series next!

“She’s shown herself to be a weirdly ethical little thing most of the time.”

“That is the most unromantic declaration of love I’ve ever heard. Or is that what you’re saying? Do you love me, Shori, or do I just taste good?”

I sighed. “They’re probably right then. It doesn’t matter. I haven’t felt inclined to tell lies. So far, my problem is ignorance, not dishonesty.” (p. 196)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply