This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

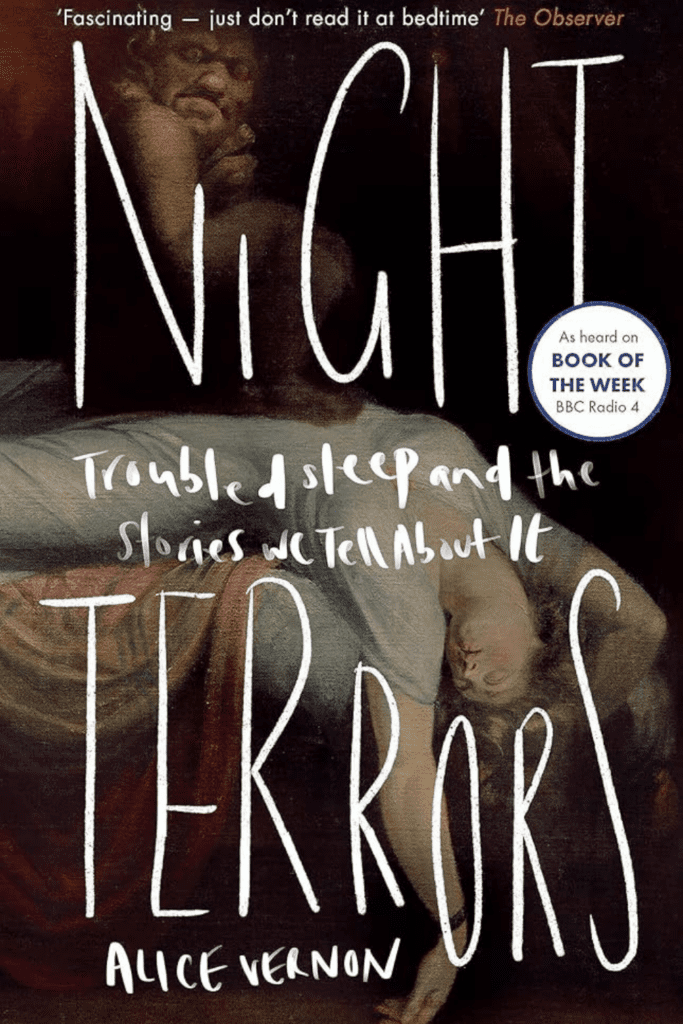

As told by its full title, “Night Terrors” is a non-fiction book about Troubled Sleep and the Stories We Tell About It. Alice Vernon, the author, recounts some of her own traumatic experiences with sleepwalking. However, she mainly surveys ‘parasomnias‘ (undesirable sleep behaviors) both through time and imagination.

- Date finished: February 2nd, 2025

- Pages: 272

- Format: Hardcover

- Form: Non-Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Non-Fiction | Science | Sleep

Buy “Night Terrors”

As mentioned above, “Night Terrors” is a non-fiction book about Troubled Sleep and the Stories We Tell About It.

I read “Night Terrors” at an apt time, having just watched the new ‘Nosferatu’ movie at the end of December 2024, suffering many months with insomnia, and my deep fascination with vampires and night haunting while writing my gothic novel on vampirism.

I’ve learned so much about night terrors! Some facets of parasomnias are much stranger than fiction. After reading the book, I view Victorian ghost stories and Gothic vampire novels differently.

Nightmares, night terrors, lucid dreams, sleep paralysis, somnambulism and hypnopompic hallucinations are some of the phenomena known as ‘parasomnias.’ Even the name evokes images of ghosts and monsters, crumbling towers and overgrown graveyards. These strange states of sleep have a profound and timeless effect on our imagination, shaping art, literature and scientific investigations, and provoking paranoia of witches and, more recently, extra terrestrial encounters. (p. 3)

From Greek and Roman antiquity – to Victorian ghost stories – to the Salem witch trials in the 17th century – to the early 19th century Franklin Arctic expedition which led to the disappearance of naval ships HMS Terror and HMS Erebus – to the world being plagued by COVID-19 dreams, Alice Vernon surveys sleep disturbances through time, imagination, and art.

Here’s an example from the Greek and Roman antiquity:

Even in antiquity, when the gods of Greek and Roman religion were a fundamental part of everyday life, stories about dreams and sleep were varied. Macrobius, a fifth-century Roman philosopher, broke sleep into five categories: prophetic vision (visio), nightmare (insomnium), ghostly apparition (phantasma), enigmatic dream (somnium), and the oracular dream (oraculum).

There is particular emphasis here on the dream as a portent.

It isn’t true to say that everyone believed that dreams were a gift from the gods, but there were numerous ideas regarding a relationship between dreams and divine influence. In ancient Greece, for example, the god of medicine, Asclepius, was believed to have a keen interest in dreams. The process known as ‘incubation’ in this era involved a sick or injured person visiting a shrine to Asclepius and sleeping there. During the night, Asclepius was supposed to either cure the persons ailment or show them a dream which instructed them on the best cure or treatment.

The ‘epiphany’ dream was rather commonly reported at this time, too. Epiphanies were dreams that were thought to be a visitation from a god, but this could be very widely interpreted — sometimes the gods didn’t actually appear as themselves, but their presence would be known by the message they gave. The philosopher Pliny, for example, wrote that when a man was afflicted by rabies, a god told his mother the cure in a dream. (p. 9)

Although the author explores the supernatural and artistic visions of night terrors, common examples taken from literature such as ‘Dracula,’ ‘Macbeth,’ ‘Jane Eyre,’ ‘The Haunting of Hill House,’ ‘A Christmas Carol,’ and more — she also goes through historical medical and psychological papers to reflect the beliefs of the time.

Ghost stories take on a different meaning if you read them with sleep disorders and hallucinations in mind. Frequently, such stories occur at night and in the bedroom. Think of Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, visited by ghosts as he passes a fitful sleep on Christmas Eve. Ghost stories — particularly Victorian ones — favour the bedchamber. It was not simply a place of sleep, but also a place of sickness (often endured under a cocktail of strong medicines) and even death.

On a thematic level, the veil between life and death was thin in the bedroom. Perhaps hypnopompic hallucinations, in this case, created a kind of vicious cycle. Stories about ghostly bedroom encounters might have fuelled night-time anxieties, and the dread of seeing a ghost might have provoked hallucinations of people. (p. 76)

For example, in Victorian society, the collective occupation was the fear of mortality, which produced haunted sleep, such as ghost stories:

Motifs of death, decay, and Gothic imagery occur again and again throughout the Census responses. Not only was life expectancy much shorter and infant mortality much higher in Victorian Britain than it is today (Victorian novelists teach us that having the window open a bit too long means certain expiration), but popular culture was rife with images of skeletons, rotting corpses, and tombstones. The ‘memento mori’ (Latin for ‘remember you are mortal’ — cheery) was an object or token, ranging from a crudely carved coffin to elaborate dioramas and clocks depicting anything from an anatomy lesson to some sort of skeleton disco. These could be carried around with people as an everyday item — cufflinks, a pocket-watch — or proudly displayed on mantelpieces and in living rooms. The wonderful Wellcome Collection in London has a vast display of memento mori, and their collection is so large that some of it is also displayed in the Science Museum’s Medicine Gallery, including Charles Darwin’s whalebone walking stick topped with a skeletal head, eyes glowing with green glass. In the present day, these icons only emerge at Halloween, but in the nineteenth century they were ubiquitous. (p. 83)

Before passing to the next section, I wanted to share one more important discovery while reading this book. I learned that many of the authors listed have themselves experienced OR purposefully provoked (through drug use and forced indigestion) troubled sleep that aided in their creative process. Here’s one rumored example:

But in all seriousness, food was considered to be the main cause of any kind of upset sleep. In my travels through old treatises, a rumour pops up on occasion: allegedly, the famous Gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe, who wrote some of the earliest novels of that movement, such as The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), deliberately ate raw steak to make herself ill and provoke inspiration through wild dreams and hallucinations. (p. 97)

In this next section, I want to briefly share what I’ve learned [underlined] about the different forms of parasomnias.

Somnambulism, commonly known as sleepwalking

Also known as somnambulism, sleepwalking is the phenomenon of moving and undertaking complex physical actions despite being asleep. These actions can range from walking across the bedroom and back to cooking a three-course meal or even driving a car. It’s a fairly common parasomnia in children, but can persist into or even develop in adulthood. Usually, the sleepwalker’s eyes are open — but with a far-away stare that can be quite disconcerting. To wake a sleepwalker during an episode can disorient or frighten them, and so it’s best to talk to the person calmly and try to guide them back to bed. Most often the episode passes without incident, but there have been famous cases in the past of violence, accidental self-harm, and even murder committed during sleep. (p. 30)

Sleep-related hallucination: hypnagogic and hypnopompic

There are two main forms of sleep-related hallucination: hypnagogic and hypnopompic. You may have heard of hypnagogic hallucinations, and have likely experienced them; they are the flashes of images or patterns that appear against our eyelids when we’re close to falling asleep. Hypnopompic hallucinations are much rarer, and involve the projection of dream-like images, feelings or sounds onto waking perception. It often occurs in the first moments after waking up; a presence such as a person, monster, or animal will appear for a second or two — long enough for the viewer to react — before disappearing. (pp. 63-64)

Sleep paralysis

Various names have been given to sleep paralysis in the past, and most of them are aligned with supernatural forces. The old name for sleep paralysis was ‘nightmare’ — a word that has now come to mean a bad dream or a generally troubled sleep. The word ‘mare’ comes from mara, an Old Norse word for a witch who would lie on people’s chests and try to suffocate them. It was also associated with a horse, possessed by witchcraft, that would come and trample the sleeper. When the episode had a sexual aspect to it, it was sometimes described as a demonic ‘incubus’ when taking a male form, or ‘succubus’ when female. Other names included being ‘hag-ridden’ or suffering from ‘wizard-pressing’ (my personal favourite — I think we need to bring this term back). These names encouraged supernatural interpretation, and further heightened the fear of witchcraft and the devil that was prevalent around Europe up to the seventeenth century. (p. 92)

Lucid dreaming

Lucid dreaming, particularly its potential for creativity and its sensation of freedom, has been cultivated in Buddhist meditation and Hindu yoga practices since the early medieval period.

It is often discussed in terms of spiritual ascension or an otherworldly power, as well as being a physiological phenomenon.

Common to both theories, however, is one aspect in particular: the ability to experience lucid dreams can be learned. (p. 201)

Beds are places of rest, safety, security, but only if your sleep is peaceful. For insomniacs, the bed is a cruel tormentor; for those of us with parasomnias, the bed is a haunted crypt. (p. 18)

Sleep paralysis was once interpreted as being ‘ridden’ by the incubus or succubus, a shadowy, impish figure that sought to squeeze the life out of its helpless victim. (p. 20)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply