This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

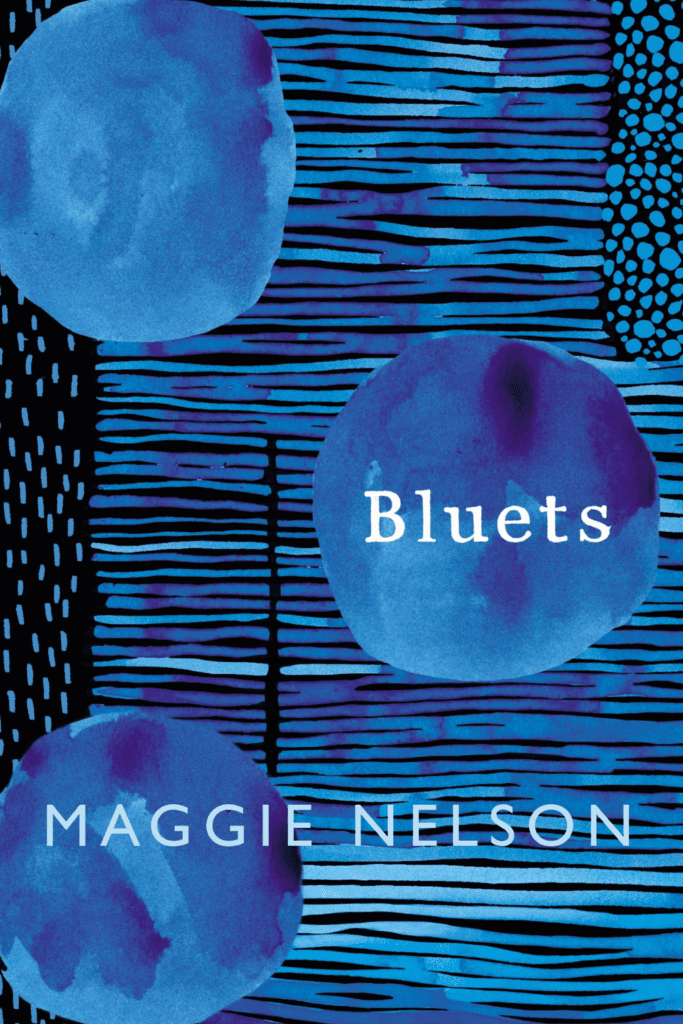

“Bluets” is a book of lyrical, meditative fragments or vignettes on the colour blue intermingled with Maggie Nelson’s feelings of love, sadness, and despair.

- Date finished: November 9th, 2024

- Pages: 112

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Non-Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Non-Fiction | Essays | Memoir

Buy “Bluets”

As mentioned above, “Bluets” is a book of lyrical, meditative fragments or vignettes on the colour blue intermingled with Maggie Nelson’s feelings of love, sadness, and despair.

“Bluets,” despite its short size, reads simultaneously as an impactful memoir and an exercise in self-introspection.

The book’s philosophical approach to examining Maggie Nelson’s emotional life through the lens of the colour blue is quite original — it is beautifully written. As a writer, I find “Bluets” an inspiring experimental read.

This is the type of book you revisit often in moments of grief, loneliness, and solitude, but also in love, hope, and beauty. Life, after all, takes on many shades of blue.

I just know that Maggie Nelson would hate that clichéd expression.

The following is less a review and more of an appreciation, in quotation, of the fragments I’ve enjoyed. I’ve tried to separate them relating to a certain thematic focus.

Quotes about loneliness and solitude:

71. I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do.

72. It is easier, of course, to find dignity in one’s solitude. Loneliness is solitude with a problem. Can blue solve the problem, or can it at least keep me company within it? — No, not exactly. It cannot love me that way; it has no arms. But sometimes I do feel its presence to be a sort of wink—Here you are again, it says, and so am I. (p. 28)

Quotes directly about the colour blue:

36. Goethe describes blue as a lively color, but one devoid of gladness. “It may be said to disturb rather than enliven.” Is to be in love with blue, then, to be in love with a disturbance? Or is the love itself the disturbance? And what kind of madness is it anyway, to be in love with something constitutionally incapable of loving you back? (pp. 14-15)

78. Once I traveled to the Tate in London to see the blue paintings of Yves Klein, who invented and patented his own shade of ultramarine, International Klein Blue (1KB), then painted canvases and objects with it throughout a period of his life he dubbed “l’époque bleue.” Standing in front of these blue paintings, or propositions, at the Tate, feeling their blue radiate out so hotly that it seemed to be touching, perhaps even hurting, my eyeballs, I wrote but one phrase in my notebook: too much. I had come all this way, and I could barely look. Perhaps I had inadvertently brushed up against the Buddhist axiom, that enlightenment is the ultimate disappointment. “From the mountain you see the mountain,” wrote Emerson. (p. 30)

145. In German, to be blue – blau sein – means to be drunk. Delirium tremens used to be called the “blue devils,” as in “my bitter hours of blue-devilism” (Burns, 1787). In England “the blue hour” is happy hour at the pub. Joan Mitchell-abstract painter of the first order, American expatriate living on Monet’s property in France, dedicated chromophile and drunk, possessor of a famously nasty tongue, and creator of arguably my favorite painting of all time, Les Bluets, which she painted in 1973, the year of my birth-found the green of spring incredibly irritating. She thought it was bad for her work.

She would have preferred to live perpetually in “l’heure de bleu.” Her dear friend Frank O’Hara understood. Ah daddy, I wanna stay drunk many days, he wrote, and did. (pp. 56-57)

146. “When a woman drinks it’s as if an animal were drinking, or a child,” Marguerite Duras once wrote. “It’s a slur on the divine in our nature.” In Crack Wars, Avital Ronell refers to Duras’s works as “alchoholizations” —as saturated, so to speak, with the substance. Could one imagine a book similarly saturated, but with color? How could one tell the difference? And if “saturation” means that one simply could not absorb or contain one single drop more, why does “saturation” not bring with it a connotation of satisfaction, either in concept, or in experience? (p. 57)

156. “Why is the sky blue?” — A fair enough question, and one I have learned the answer to several times. Yet every time I try to explain it to someone or remember it to myself, it eludes me. Now I like to remember the question alone, as it reminds me that my mind is essentially a sieve, that I am mortal. (p. 62)

157. The part I do remember: that the blue of the sky depends on the darkness of empty space behind it. As one optics journal puts it, “The color of any planetary atmosphere viewed against the black of space and illuminated by a sunlike star will also be blue?” In which case blue is something of an ecstatic accident produced by void and fire. (p. 62)

Quotes about writing:

183. Goethe also worries over the destructive effects of writing. In particular, he worries over how to “keep the essential quality [of the thing] still living before us, and not to kill it with the word.” I must admit, I no longer worry much about such things. For better or worse, I do not think that writing changes things very much, if at all.

For the most part, I think it leaves everything as it is. What does your poetry do? -I guess it gives a kind of blue rinse to the language (John Ashbery). (p. 74)

184. Writing is, in fact, an astonishing equalizer. I could have written half of these propositions drunk or high, for instance, and half sober; I could have written half in agonized tears, and half in a state of clinical detachment. But now that they have been shuffled around countless times—now that they have been made to appear, at long last, running forward as one river-how could either of us tell the difference? (p. 74)

185. Perhaps this is why writing all day, even when the work feels arduous, never feels to me like “a hard day’s work.” Often it feels more like balancing two sides of an equation-occasionally quite satisfying, but essentially a hard and passing rain. It, too, kills the time. (pp. 74-75)

186. Another form of aggrandizement: to make a substance into a god, even if one eventually condemns it as a false one. It was in an effort to puncture precisely this sort of embellishment that the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire opted to call his 1913 book of poems not L’eau de vie, but the more precise, much “cooler,” Alcools. (p. 75)

8. Do not, however, make the mistake of thinking that all desire is yearning. “We love to contemplate blue, not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it,” wrote Goethe, and perhaps he is right. But I am not interested in longing to live in a world in which I already live. I don’t want to yearn for blue things, and God forbid for any “blueness.” Above all, I want to stop missing you. (p. 4)

224. Recently I found out that “les bluets” can translate as “cornflowers.” You might think I would have known this all along, as I have been calling this book “Bluets” (mis-pronounced) for years. But somehow I had only ever heard, “a small blue flower with a yellow center that grows abundantly in the countryside of France.” I thought I’d never seen it. (p. 90)

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply