This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

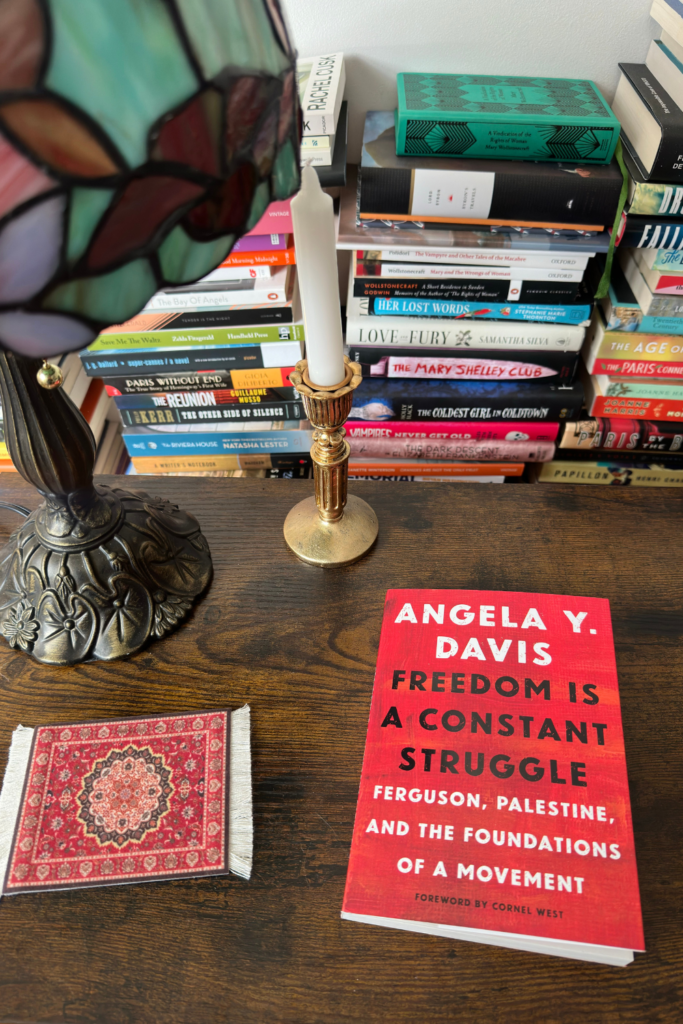

“Freedom Is a Constant Struggle” is a book of collected interviews and speeches by Angela Davis, published a decade ago but still insanely prevalent in today’s society. Davis collects her talks about the importance of intersectionality, freedom for Palestine, the voices of black feminists, and the prison abolitionist movement.

- Date finished: November 8th, 2024

- Pages: 158

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Non-Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Non-Fiction | Politics | Feminism

As stated above, “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle” is a book of collected interviews and speeches by Angela Davis, published a decade ago but still insanely prevalent in today’s society. Davis talks about the importance of intersectionality, freedom for Palestine, the voices of black feminists, and the prison abolitionist movement.

“Freedom Is a Constant Struggle” is hands-down a must-read book. Everyone – especially those residing in North America – should read some Angela Y. Davis.

Despite its short format of interviews and talks, I’ve learned a lot. Davis concisely tackles the importance of prison (a model upheld by white supremacy, echoing black slavery) abolishment, freedom for Palestine, and the BDS movement — boycott, divestment, and sanctions.

Before reading this book, I wasn’t much aware of the prison-industrial complex and what it meant for the world. Davis highlights the great dangers of the privatization and capitalist infrastructures that fond the genocide in Gaza and the high incarceration rates in America:

You recently gave a talk in London about Palestine, G4S (Group 4 Security, the biggest private security group in the world), and the prison-industrial complex. Could you tell us how those three are linked?

Under the guise of security and the security state, G4S has insinuated itself into the lives of people all over the world especially in Britain, the United States, and Palestine. This company is the third-largest private corporation in the world after Walmart and Foxconn, and is the largest private employer on the continent of Africa. It has learned how to profit from racism, anti-immigrant practices, and from technologies of punishment in Israel and throughout the world. G4S is directly responsible for the ways Palestinians experience political incarceration, as well as aspects of the apartheid wall, imprisonment in South Africa, prison-like schools in the United States, and the wall along the US-Mexico border. Surprisingly, we learned during the London meeting that G4S also operates sexual assault centers in Britain. (p. 5)

It is disheartening to learn this. All of these years we’re told by our government, conditioned by society, to believe that prisons are primarily for the ‘safety’ of the people when in actuality it’s another big ever-expanding monopoly that echoes modern slavery and is fuelled by racism and capitalism:

How profitable is the prison-industrial complex? You often have said it is the equivalent of “modern slavery.”

The global prison-industrial complex is continually expanding, as can be seen from the example of G4S. Thus, one can assume that its profitability is rising. It has come to include not only public and private prisons (and public prisons, which are more privatized than one would think, are increasingly subject to the demands of profit) but also juvenile facilities, military prisons, and interrogation centers. Moreover, the most profitable sector of the private prison business is composed of immigrant detention centers. One can therefore understand why the most repressive anti-immigrant legislation in the United States was drafted by private prison companies as an undisguised attempt to maximize their profits. (p. 6)

Now, I will admit it’s hard to reconcile with the truth. It is even harder to believe that we can live in a world without prisons. However, Davis remains hopeful that such an endavour is possible. I’m coming to terms with the fact that there’s a discrepancy between people’s knowledge of the sinister nature of the prison-industrial complex and their concern for their safety. I believe that if more people were made aware and joined the prison abolitionist movement, we could get there:

Is a prison or jail free society a utopia, or is it possible? How would that work?

I do think that a society without prisons is a realistic future possibility, but in a transformed society, one in which people’s needs, not profits, constitute the driving force. At the same time prison abolition appears as a utopian idea precisely because the prison and its bolstering ideologies are so deeply rooted in our contemporary world. There are vast numbers of people behind bars in the United States some two and a half million and imprisonment is increasingly used as a strategy of deflection of the underlying social problems: racism, poverty, unemployment, lack of education, and so on. These issues are never seriously addressed. It is only a matter of time before people begin to realize that the prison is a false solution. Abolitionist advocacy can and should occur in relation to demands for quality education, for antiracist job strategies, for free health care, and within other progressive movements. It can help promote an anticapitalist critique and movements toward socialism. (pp. 6-7)

Furthermore, Angela Y. Davis reminds us of the importance of asking the right questions. To interrogate the roots of the crime and violent behaviours in our society to uncover real solutions instead of perpetuating more violence in a violent institution (e.g., prisons.) She interrogates:

Why is that person bad? The prison forecloses discussion about that. What is the nature of that badness? What did the person do?

Why did the person do that? If we’re thinking about someone who has committed acts of violence, why is that kind of violence possible?

Why do men engage in such violent behavior against women? The very existence of the prison forecloses the kinds of discussions that we need in order to imagine the possibility of eradicating these behaviors.

Just send them to prison. Just keep on sending them to prison.

Then of course, in prison they find themselves within a violent institution that reproduces violence. In many ways you can say that the institution feeds on that violence and reproduces it so that when the person is released he or she is probably worse. (p. 22)

The next part is a sobering reality. Corporations benefit from prisoners. At this point, the whole starts to form together. The governing body never cared about safety or security, they cared about bodies. They care about labour and money and they found their perfect scapegoat, one which society would never bat their eyes:

It’s [the prison-industrial complex] a big money-making business.

It’s totally a money-making business.

They do need prisoners, right?

Absolutely. Especially given the increasing privatization of prisons, but there is privatization beyond private prisons. It consists of the outsourcing of prison services to all kinds of private corporations, and these corporations want larger prison populations. They want more bodies. They want more profits. And then you look at the way in which politicians always note that, whether there is a high crime rate or not, law-and-order rhetoric will always help to mobilize the voting population. (p. 24)

Angela Y. Davis reminds us of the importance of the voices of prisoners and their involvement in the abolitionist movement. She insists that they are crucial and should be equals, i.e., treated like human beings with rights, in the prison reform movement:

What about prisoners in prison? Can you talk about agency and struggles, prisoners and their own struggles?

Whenever you conceptualize social justice struggles, you will always defeat your own purposes if you cannot imagine the people around whom you are struggling as equal partners. Therefore if, and this is one of the problems with all of the reform movements, if you think of the prisoners simply as the objects of the charity of others, you defeat the very purpose of antiprison work. You are constituting them as an inferior in the process of trying to defend their rights.

The abolitionist movement has learned that without the actual participation of prisoners, there can be no campaign. That is a matter of fact. Many prisoners have contributed to the development of this consciousness: the abolition of the prison-industrial complex. It may not always be easy to guarantee the participation of prisoners, but without their participation and without acknowledging them as equals, we are bound to fail. (p. 26)

We are used to equating prison = bad people. Beyond thinking of crime and punishment, Davis reminds us that we need to think of education, literacy, homelessness, mental health care, health care, and racism. Or else, it is no wonder that the prison system reflects modern-day slavery, and the death penalty being it’s chief issue:

The groundwork has to be done on a daily basis …

The prison abolitionist movement is also incorporating demands for the abolition of the death penalty. We need to develop broader resistance to the death penalty. In the case of Mumia it worked on a small scale he was removed from death row, but we should have been able to use that as a launching pad for Mumia’s full freedom, for abolition of the death penalty, and, of course also of prisons.

Capital punishment remains a central issue. We need to popularize understandings of how racism underwrites the death penalty, and so many other institutions. The death penalty is about structural racism and it incorporates historical memories of slavery. We cannot understand why the death penalty continues to exist in the United States in the way that it does, without an analysis of slavery. So this is again one of the really important issues confronting us. But I think we will need a mass movement and a global movement to finally remove the death penalty from the books. (p. 30)

Furthermore, Davis reminds the importance of ‘intersectionality’ in our activism – to see these issues on a worldwide scale, intersecting between the injustices of race, class, and gender:

So it’s all great, but in your opinion, what could we do to strengthen the pro-justice movement even more, in the US? And the same question applies to the whole world I think.

Well, I think that we constantly have to make connections. So that when we are engaged in the struggle against racist violence, in relation to Ferguson, Michael Brown, and New York, Eric Garner, we can’t forget the connections with Palestine. So in many ways think we have to engage in an exercise of intersectionality. Of always foregrounding those connections so that people remember that nothing happens in isolation. That when we see the police repressing protests in Ferguson we also have to think about the Israeli police and the Israeli army repressing protests in occupied Palestine. (p. 45)

Returning to ‘safety,’ we are faced with a grim reality: the militarization of the police. U.S. officers are trained in Israel by the Israeli Army – the same Army that is actively still committing genocide of the Palestinian people in Gaza. And thus, police officers are shown to shoot to kill, not to protect or conserve life. The G4S private security company further exacerbates this problem:

G4S is especially important because it participates directly and blatantly in the maintenance and reproduction of repressive apparatuses in Palestine prisons, checkpoints, the apartheid wall, to name only a few examples. G4S represents the growing insistence on what is called “security” under the neoliberal state and ideologies of security that bolster not only the privatization of security but the privatization of imprisonment, the privatization of warfare, as well as the privatization of health care and education. (p. 55)

The real ‘war on terror’ is produced and manufactured by these privatized companies, endorsed by the racist unapologetic agenda of greedy Western governments:

This use of the war on terror as a broad designation of the project of twenty-first-century Western democracy has served as a justitication of anti-Muslim racism; it has further legitimized the Israeli occupation of Palestine; it has redefined the repression of immigrants; and has indirectly led to the militarization of local police departments throughout the country. Police departments including on college and university campuses have acquired military surplus from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan through the Department of Defense Excess Property Program. Thus, in response to the recent police killing of Michael Brown, demonstrators challenging racist police violence were confronted by police officers dressed in camouflage uniforms, armed with military weapons, and driving armored vehicles. (p. 79)

And we see its rippling effects worldwide. The populace is encouraged to point its ignorant fear-induced, trembling, angry fingers at immigrants instead:

This appalling treatment of undocumented immigrants from the UK to the US compels us to make connections with Palestinians who have been transformed into immigrants against their will, indeed into undocumented immigrants on their own ancestral lands.

I repeat on their own land. G4S and similar companies provide the technical means of forcibly transforming Palestinian into immigrants on their own land. (p. 58)

In this way, the real terrorists have always been the countries upholding white supremacy, endorsing genocide, and hoarding stolen lands (Canada, the United States of America, Israel, and Great Britain to name a few). Angela Y. Davis herself was placed on the U.S Ten Most Wanted list for her activism:

And I should say parenthetically, when I learned about this in May, I remembered when I was placed on the Ten Most Wanted. I didn’t make the Ten Most Wanted terrorist list, I think they didn’t have one at that time, but I made the Ten Most Wanted criminal list. And I was represented as armed and dangerous. And you know one of the things I remember thinking to myself was, what is this all about? What could I possibly do? And then I realized it wasn’t about me at all; it wasn’t about the individual at all. It was about sending a message to large numbers of people whom they thought they could discourage from involvement in the freedom struggles at that time.

Assata Shakur is one of the ten most dangerous terrorists in the world according to Homeland Security and the FBI, and then when I think about the violence of my own youth in Birmingham, Alabama, where bombs were planted repeatedly and houses were destroyed and churches were destroyed and lives were destroyed, and we have yet to refer to those acts as the acts of terrorists.

Terrorism, which is represented as external, as outside, is very much a domestic phenomenon. Terrorism very much shaped the history of the United States of America. (pp. 74-75)

In such matters, Angela Y. Davis reminds us that “the personal is political,” an old feminist adage that remains true. (Just look at the state of U.S. politics in 2024, a decade after this collection was published.) The abolitionist mission shares the same sphere as the feminist mission:

So bringing feminism within an abolitionist frame, and vice versa, bringing abolition within a feminist frame, means that we take seriously the old feminist adage that “the personal is political” The personal is political everybody remembers that, right? The personal is political. We can follow the lead of Beth Richie in thinking about the dangerous ways in which the institutional violence of the prison complements and extends the intimate violence of the family, the individual violence of battery and sexual assault. We also question whether incarcerating individual perpetrators does anything more than reproduce the very violence that the perpetrators. have allegedly committed. In other words criminalization allows the problem to persist. (p. 105)

Davis further explains that violence – against women and minorities – has made its way from the public to the private and the privatized systems in place:

And it seems to me that people who are working on the front line of the struggle against violence against women should also be on the front line of abolitionist struggles. And people opposed to police crimes, should also be opposed to domestic what is constructed as domestic violence. We should understand the connections between public violence and private or privatized violence.

There is a feminist philosophical dimension of abolitionist theories and practices. The personal is political. There is a deep relationality that links struggles against institutions and struggles to reinvent our personal lives, and recraft ourselves. We know, for example, that we replicate the structures of retributive justice oftentimes in our own emotional responses. Someone attacks us, verbally or otherwise, our response is what? A counterattack. The retributive impulses of the state are inscribed in our very emotional responses.

The political reproduces itself through the personal. This is a feminist insight a Marxist-inflected feminist insight-that perhaps reveals some influence of Foucault. This is a feminist insight regarding the reproduction of the relations that enable something like the prison-industrial complex. (p. 106)

More and more, I’m reminded of North Americans’ second greatest threat: apathy. James Baldwin warned us more than half a century ago: “I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country.” I watch and listen as generations before and after mine (I was born in 1997) face a dreadful resignation and collective hopelessness of our power towards big corporations and big technologies. The important activist work of the few is constantly being drowned out.

And yet, I have never seen so much mobilization before for the Palestinian cause in its 75-year fight for survival, which reminds us that there is still hope. We must overcome apathy, we must continue to get involved, share books and knowledge, and lead by example. Our voices must continue to unite and demand freedom for all.

All in all, I could not cover everything that has been written in this book. It has opened my eyes, transformed and challenged old beliefs I’ve held regarding prisons. I look forward to reading – and learning – more from Angela Y. Davis’s works.

Everyone and everything tells you that “outside” you will not succeed, that it is too late, that we live in an epoch where a revolution cannot happen anymore. Radical changes are a thing of the past. You can be an outsider, but not outside the system, and you can have political beliefs, even radical ones, but they need to stay within the bounds of the permissible, inside that bubble that has been drawn for you by the elites. (pp. ix and x)

The party, but more importantly, the message, the idea the party embodies, is under threat. The concept that another way of organizing our lives collectively is possible, that we can be ruled by each other, the 99 percent, instead of technocrats, banks, and corporations. As I write this, the hope that finds expression in the streets and homes all over Greece is a movement. A movement in the midst of a huge loss of material wealth for ordinary Greeks. But there’s a message there for everyone and it is that people can unite, that democracy from below can challenge oligarchy, that imprisoned migrants can be freed, that fascism can be overcome, and that equality is emancipatory.

The powerful have sent us a message: obey, and if you seek collective liberation, then you will be collectively punished. In the case of Europe, it’s the violence of austerity and borders where migrant lives are negated, allowed to drown in sea buffer zones. In the case of the United States, Black and Native lives are systematically choked by an enduring white supremacy that thrives on oppression and settler colonialism, and is backed by drones, the dispossession of territory and identity to millions, mass incarceration, the un-peopleing of people, and resource grabs that deny that indigenous lives matter and that our planet matters. All around us and up close, we are being told not to care. Not to collectivize, not to confront. (pp. x and xi)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply