This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

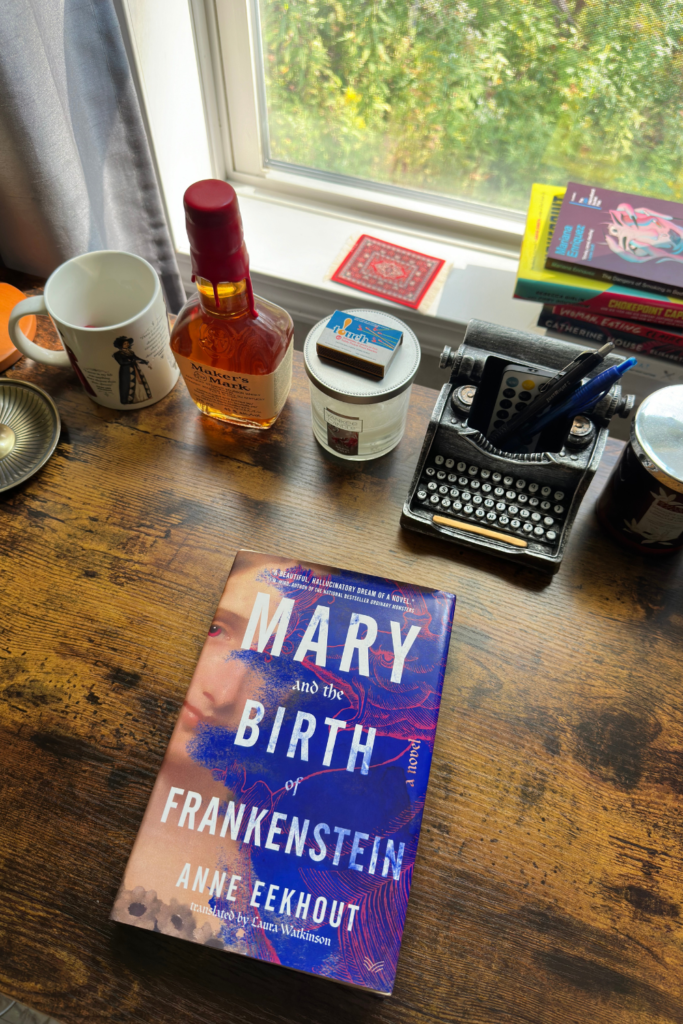

“Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein“ is a reimagining of Mary Shelley’s life and the creation of her groundbreaking novel “Frankenstein.”

- Date finished: September 14th, 2024

- Pages: 320

- Format: Hardback

- Form: Novel

- Language read: Translated in English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Historical Fiction | Gothic | LGBT

“Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein“ is a dual-timeline reimagining of Mary Shelley’s life. In the first timeline, we follow Mary and her friends (including the notorious Lord Byon) at Lake Geneva in 1816, during the “year without summer.” In the second timeline, we follow a younger Mary, aged fourteen in 1812, during her visit to the Baxter family in Dundee, Scotland.

Previously this year, I read “Romantic Outlaws,” a book that deeply touched and transformed me. Craving more in regards to Mary Shelley’s life (real or imagined), I decided to pick up “Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein.” I am so glad I did; this book is now also one of my 6-star books. This means that it’s a favourite, favourite book. The closest to perfection type of books.

Anne Eekhout beautifully and accurately depicts the intricate relationships between Mary Shelley, her step-sister Claire, Percy Shelley, John Polidori, and Lord Byron. It truly felt like reading a fictionalized, focused recount of Mary’s life and her creation of Frankenstein.

“ACLAP OF THUNDER, Percy turns over with a groan. His knee jabs Mary’s side. In the moonlight shining through the crack of the shutters, she can see his face. Her tempestuously beautiful elf. She knows no other man who, with such fine features and translucent skin, like a satin moth, almost like a girl, holds such a strong attraction for her.

And she is his great love. She does know that, but it is not easy. The fact that his philosophy is not quite hers-maybe in theory, yet not in practice puts their love to the test again and again. Perhaps it is tolerable that, now and then, he loves another woman. Perhaps.

But that it does not bother him, that he actually encourages her to share her bed with another man—that tortures her soul. At the same time, she sees how he looks when she talks to Albe about his poems, or about her father. Those are the moments when jealousy strikes him, she thinks, a cold fear in his eyes. The jealousy he feels then has nothing to do with her. Percy is not afraid that she will choose Albe over him. He is afraid that Albe will choose her over him. That the great, wild poet Lord Byron finds her more interesting than Percy Shelley, who still has so much to learn. Does he have enough talent? Eloquence? Percy has pinned his hopes on Albe.

Could he show him the light? Could Albe give him advice, become his mentor, maybe even his friend? Very occasionally, when Percy is so insecure-oh, he does not say so, but she can see it, the faint hope in his eyes, the childish impatience in his movements- then she fears for a moment that she does not love him.

She kisses him softly on the cheek. He groans again. Turns over. The knee in her side disappears. And slumber, finally, approaches. She feels the arms of sleep unfolding like wings, wrapping her tightly, protectively, not unpleasantly, and taking her consciousness away.” (pp. 4-5)

Essentially, this is a great work of imagination. And not only that, this is a wonderful book about imagination and the necessity of imagination in the creative journey.

We witness the first few rays of Mary’s imagination as she is transported to the Baxter family in Dundee, Scotland. The Baxter family is grieving their matriarch. Mary is closest in age and acquaintance to the youngest, depressive daughter. Isabella becomes Mary’s confidant and brief lover. Together, the young girls through their grief and their heightened imagination conjure things real and imagined. They are plunged in the world of daydreams and nightmares, where Scottish myths and monsters come to life.

“It is not that I am uninterested in the world outside, God knows that I am. But I have become aware of an ever-increasing interest in my own world.

The dreams I have, the nightmares, my daydreams. I notice that the writers in my books have brains that work just like mine. A brain that connects what has never been connected, what perhaps is not supposed to be connected.” (p. 21)

The Baxter family has a tradition of telling stories around the hearth on Fridays. During this tradition, we witness young Mary develop her talents and confidence as a storyteller.

“I was proud of myself for inventing something that gave people pleasure. I had taken something from real life and twisted it and spun it out until there was more to it than had really happened.

Until it was more than the truth.” (p. 36)

We also understand that men, like her father and Percy, do not experience the same kind of acute grief and loneliness. This is apparent because the men – William Godwin (her father), Mr. Booth (previously married to Isabella’s elder sister, Margaret, before she passed), and Percy Shelley (Mary’s lover and father of her children) all find ways to easily replace the women they claim to love by effortlessly remarrying or in Percy’s case, also engaging in extramarital affairs – enacting the “free love” concept. A concept, in which, after reading “Romantic Outlaws” is better in theory than practice. Even Mary’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, felt depressive and suicidal after the father of her first child, Fanny (half-sister of Mary Shelley,) was parading around with other women, discarding Wollstonecraft and his child.

“You both believe in free love, don’t you?”

She doubts whether they believe in free love. Increasingly she thinks that believing in free love is like believing in God. It is an ideal, the ideal. But ultimately, it does not work. Cannot work. You lose something, every time you give yourself and once again stand alone. Without illusions. Percy would laugh at her. He is the most fervent atheist she knows. And yet the analogy is right as far as she is concerned. Maybe free love does not work for her because Percy is the only one she wants to love.

“Yes,” she says. “Absolutely.”

“I think it’s beautiful,” says John. “You and Percy and Claire. The ease with which you get along.” (p. 160)

Men don’t play by the same rules. Lord Byron impregnates Claire and drives her mad because he’s horrible to her, leading her on and then discarding her when he’s bored or annoyed. We come to understand that being beautiful and securing a marriage are still the primary means for a woman to survive (despite Wollstonecraft’s revolutionary work “A Vindication of the Rights of Women.”) Even if both Marys are great thinkers and writers, they are expected to be beautiful and motherly first.

“My father did not concern himself with it [her scars]. He has never had much interest in appearance. Perhaps he does not know how much beauty matters in the life of girls, of women. No, I am sure he is aware. But it will be something he disapproves of. And although I understand it, his arrogance annoys me. No woman alive can allow herself the luxury of not caring about her appearance. The sheer fact that only a man may say beauty does not matter because it should not matter only goes to show the extent to which—unfortunately—he is wrong.” (p. 19)

“She [Isabella] looked at me, and I saw that she still believed in such things. She was seeking my agreement. But I was thinking about my father. My father, a man of the world. My father, who knew everything, who debated everything, who could fathom everything with such evident self-assurance. He knew so much because he read and wrote, and wrote and read, more than anyone else. I had always relied on him, he knew what was true, what could exist. He was my point of reference. But suddenly I realized how far away he was. That I was in a new world, with different people, different stories, and different rules. In a way, my father was now a story. The story lived in London, sending its daughter the occasional letter. The story was one of order and reason. It loved its daughter’s mind, but not her imagination. And Mama. Mama was a different story. Mama was a nonexistent story about fairy tales at bedtime, the sweetest kiss, the softest arm, never leave, stay forever, the hand that would always be there, because mothers do not die. If mothers could die, then there was something wrong with the world.” (p. 87)

Mary Wollstonecraft, and then her daughter Mary Godwin (known mostly as Mary Shelley), are shunned by society for advocating for “free love” and for being established women writers. For these same reasons, we understand that Lord Byron only respects Mary Shelley because she’s a talented writer and her mother was the legendary Wollstonecraft.

Let us consider this passage set in Lake Geneva when 18-year-old Mary is finally crawling out of her deep depression from losing her first daughter Clara (meanwhile, Percy is having an affair with her step-sister Claire.) She feels a tiny semblance of joy when she’s finally writing again – what we know will become her magnum opus “Frankenstein.” After all, Byron had challenged everyone to write their best ghost story. And yet, Percy reproaches Mary when she finally does take the time for herself to write:

“What?” she says. William continues to drink.

“You are not here.” He [Percy] shifts position. His elbow nudges her arm, startling William.

They do not look at each other.

“I am always here.” She feels it again, the anger, hot and sticky in her chest.

“Your thoughts. You aren’t with us.” The cold reproach buzzes around them.

Mary feels muscles she does not recognize, muscles tensing, bulging in the space between guilt and envy. And she certainly wants to say why that is. She wants to say that she is writing, that she is finally, finally writing, but she cannot. It is the thing that is inside her, that is slowly taking on life, that is preventing her from speaking. It is still too early, it is premature. Like her little-far too little girl, who already had to live even though she had not yet been able to drink in enough life. She was not yet full and she died, and that is what will happen to this story if she brings it into the world before it is ready, before it has been able to grow, to become life-size, before it has decided to be beautiful or ugly, loving or hideous, before it has been able to grow into exactly what it is in essence: a screaming vessel full of life, so deep that even she does not know its bottom. (p. 214)

Between past and present timelines of Mary Shelley’s life, marked intentionally by the changes of narrative voice (first person POV ‘I’ to third person POV ‘she,’) all of her experiences of grief, anger, loneliness, discovery [Galvani’s work], and imagination converge and merge to create her spectacular “Frankenstein.”

“Mary leans sideways in her chair and closes her eyes. Her story will be about the most frightening thing in existence. Longing, loss, grief. But there is still so much in her way that she cannot push aside. It has been there for a long time, the idea. It has existed for many centuries, ever since the earth awoke, and still it roams the word. It has seen her. It has chosen her. But the time is not ripe or she does not dare to take a look. Because if she looks, she will have to see everything. Not only the beautiful truth, wrapped in a story, trembling with wonder, ancient yet newly born, but also the cruelty, the defiance, that which screams and shrieks at her to open her eyes. And all of it is true.” (pp. 112-113)

“There are, in essence, two reasons to be unhappy. The first, of course, is death. The knowledge that everything is ultimately meaningless, as it is finite. That everything that has once been will one day be no longer makes it, by definition, futile. Even so, it feels significant when a loved one dies. The discrepancy— that is where the pain is.

She knows all about that. And everyone who has ever lived knows it. And that is in fact the second reason: life. Life is all there is, all we have, and that makes it of the utmost importance. Of such importance, and we suffer. If it is not the suffering of the body, then it is the suffering of the spirit. People are born with a will. It is the driving force behind their lives. But do people ever get what they want? In rare cases. And then? Then they want more of it. Or of something else. Satisfied people do not exist.” (p. 155)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

[…] You can read my book review here. […]