This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

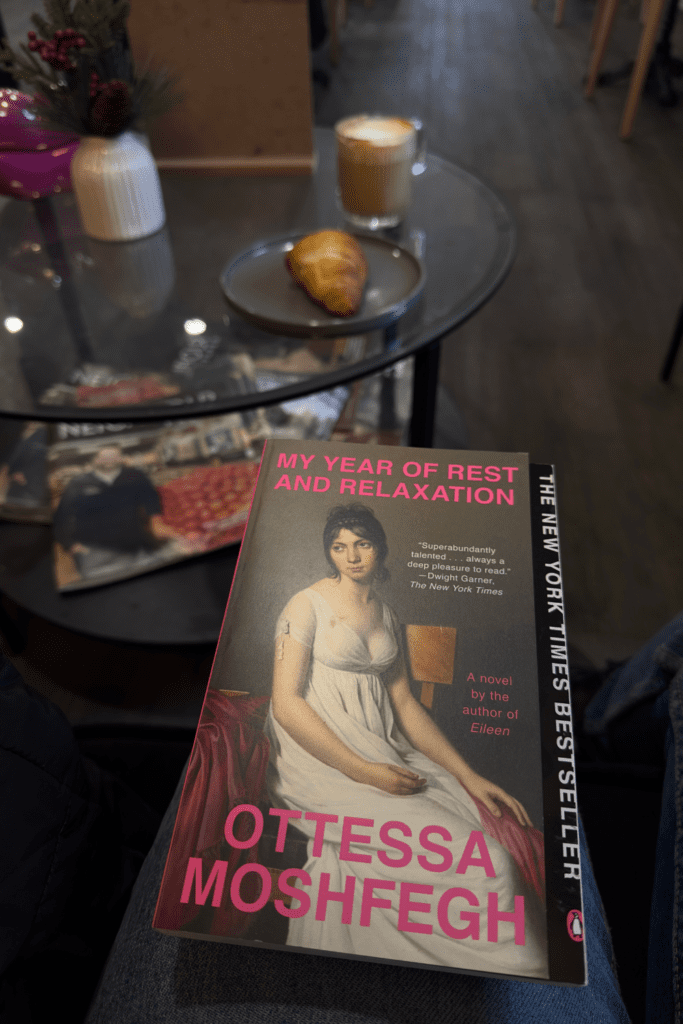

“My Year of Rest and Relaxation” is a literary fiction novel following a depressed main character who chooses to ‘rest’ (i.e., hibernate) for an entire year.

- Date finished: January 4th, 2024

- Pages: 289

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Novel

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Literary Fiction | Contemporary | Mental Health

Set at the backdrop of the turn of the century, “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” follows a privileged narrator (thin, pretty, white, rich, you get the gist) who hibernates in a drug-induced state for a year in her paid-for Upper East Side apartment. On the surface, she has everything any girl wants. But through the cracks, we meet a character who’s deeply flawed and terribly, terribly alone.

“My Year of Rest and Relaxation”, at its core, is a story about mental health and grief. Despite the main character’s many privileges, it is apparent that relationship problems, grief, and mental illness can disrupt anyone’s inner ecosystem.

This was my first experience reading an Ottessa Moshfegh book and I am glad to announce that I was not disappointed. If anything, this book reminded me of the power of good writing and strong storytelling given that the premise can be quite wanting (i.e., main character hibernating for a year.) Instead, this novel is jam-packed with the intricacies of human behavior and the complexities of our innermost psyche.

Funny – not-so-funny – story for me: after reading this, I started suffering from insomnia again. If you’re wondering whether I’m doing better (I am, but most weeks it’s a losing battle.) This book might’ve cursed me. Do I mind? Not really. There are worse ways to be cursed.

As I said, Moshfegh is wonderful at creating intimate, deep character sketches. We see this at play both with the main character and her at-times friend, at-times nemesis, Reva. We understand the latter to be a deeply insecure, vulnerable people pleaser. She also wishes to be as beautiful, rich, and thin as the main character. Whereas the former is a privileged bigot. Essentially, they are doomed to complement each other. The avoidant and the anxious. The insecure and the arrogant.

However, through uncovering the narrative past, we understand that the main character suffers from not being loved with a capital L. After losing both of her parents, the grief annihilates her, and as a result, tips the scale of the friendship’s power imbalance.

“Rejection, I have found, can be the only antidote to delusion.” p. 153

Therefore, she is desperate to cling to some semblance of love. She clings to this big-shot Wall Street asshole called Trevor. She clings to the past, to her family home. She even clings to her VHR player to watch old comforting VHS tapes of Whoopi Goldberg even if she can afford the more à la mode DVD player. She clings to familiarity because she does not have the privilege to be cemented to the world, to be loved.

In some ways, you can’t help feeling bad for her. (A lot of reviewers and readers don’t at all – and I can understand that sentiment as well.) She’s the typical person that has all of the resources available with no way to be ‘resourceful’ herself. But isn’t that the nature of depression and grief? I mean, at least she can afford her pills and therapy bill. Most of us can’t. I know I can’t.

We understand that grief delivers the last blow that provokes her to seek this quest into oblivion. But some of this suffering is self-manufactured. Despite having all of the financial resources, she brands herself as talentless, she has “no talent” (p. 16) to be an artist. To an extent, being unlikeable is her only talent and the only thing she retains from her toxic, traumatic relationship with her now-dead mother.

Not knowing how to build and sustain good healthy relationships is a big disadvantage. So is not having a family and support system. This cold reserve, being unloved, she learns young from her parents. This also explains her appeal to douchebag Trevor. She respects him only because he can manipulate her (p. 34.) And it’s the only time she can simultaneously punish and feed her ego, as well as repeat familiar patterns. Trevor being the one to survive the terrors of the Two Towers further reinforces the banality and absurdism of real life and the main character’s own life.

Reva is an interesting addition to the narrative. Because she’s real and cements the main character to reality in a tangible way. Reva does so by recognizing her flaws and the main character’s flaws. Her tragic 9/11 death leaves the readers feeling bereft. Tragedy, on the other hand, does remind us that we are alive. But personal tragedies (e.g., the death of a parent, breakups, etc.) can have the opposite effect.

Another overarching topic of this novel is the main character’s mommy issues. Her therapist, Dr. Tuttle, becomes a surrogate mother figure in her life. The main character gets her pills to become cold and mechanical like her mother. Unfortunately for Reva, the main character’s full range of abandonment-resentment issues (that is very prone to girls with mommy issues) acutely manifests itself around her:

“I was both relieved and irritated when Reva showed up, the way you’d feel if someone interrupted you in the middle of suicide. Not that what I was doing was suicide. In fact, it was the opposite of suicide. My hibernation was self-preservational.

I thought that it was going to save my life.” (p. 7)

In the end, there is a metamorphosis, albeit a slight one. The unnamed main character emerges from her self-induced slumber, sells her parents’ house, sheds skin, and starts to feel again. But the reader is left to feel numb, unsettled by the ending.

Personally, the book reminded me of my many years of dealing with dissociation and depersonalization. In that regard, the novel does a fantastic job depicting this separation between the real and the dissociative state.

You can also watch my reading vlog where I discuss both “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” and “Stoner”:

“Oh, sleep. Nothing else could ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking consciousness.”

“Sleep felt productive. Something was getting sorted out. I knew in my heart—this was, perhaps, the only thing my heart knew back then—that when I’d slept enough, I’d be okay. I’d be renewed, reborn. I would be a whole new person, every one of my cells regenerated enough times that the old cells were just distant, foggy memories. My past life would be but a dream, and I could start over without regrets, bolstered by the bliss and serenity that I would have accumulated in my year of rest and relaxation.”

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply