This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

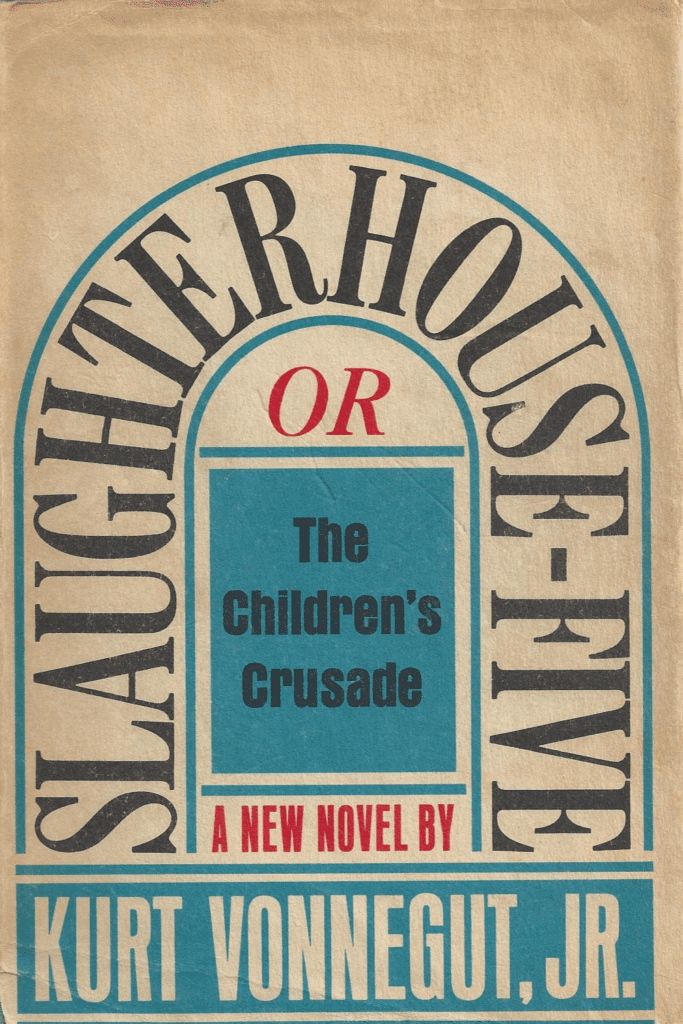

“Slaughterhouse-Five” is an anti-war novel about the often overlooked tragedy that was the Bombing of Dresden in WWII. In this fictionalized account, Vonnegut transforms his experience by creating the sensitive character of Billy Pilgrim, a barber’s son drafted into the war and then abducted by friendly aliens when he becomes ‘unstuck in time.’

- Date finished: February 9th, 2025

- Pages: 275

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Classics | Science Fiction | War

As mentioned, “Slaughterhouse-Five” is an anti-war novel about the often overlooked tragedy that was the Bombing of Dresden in WWII. In this fictionalized account, Vonnegut transforms his experience by creating the sensitive character of Billy Pilgrim, a barber’s son drafted into the war and then abducted by friendly aliens when he becomes ‘unstuck in time.’

The intent of “Slaughterhouse-Five” is clear: it’s an anti-war book. Vonnegut crafts the character Billy Pilgrim to illustrate the horrors of war juxtaposed with a passive and sensitive man who surrenders and gives up easily. When Billy Pilgrim becomes unstuck in time, he wants to bring world peace as he has seen with the aliens (called Trafalmadorians) who have abducted him.

All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his.

Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war.

And so on. I’ve changed all the names. (p. 1)

This book has an interesting narrative frame that works to highlight Vonnegut’s intent: part anti-war book, part autobiographical elements, and part time travel novel.

The use of time travel as the vehicle for PTSD is quite significant. While reading this book, I was researching to further my time travel novel that has been abandoned for nearly 7 years on my computer. Time Travel is about the past and the future, and grief and loss remain at the narrative’s epicenter of the present moment. In time travel literature, it is not uncommon to encounter injustice and memory in a different, reconstructive light.

In this framework, Vonnegut has to deliver what many have failed at before: writing an anti-war book.

Over the years, people I’ve met have often asked me what I’m working on, and I’ve usually replied that the main thing was a book about Dresden.

I said that to Harrison Starr, the movie-maker, one time, and he raised his eyebrows and inquired, “Is it an anti-war book?”

“Yes,” I said. “I guess.”

“You know what I say to people when I hear they’re writing anti-war books?”

“No. What do you say, Harrison Starr?”

“I say, ‘Why don’t you write an anti-glacier book instead?’”

What he meant, of course, was that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers. I believe that, too.

And even if wars didn’t keep coming like glaciers, there would still be plain old death. (pp. 3-4)

Not only is he tasked to fulfill this promise to his readers but to Mary, Bernard’s wife, a real-life person and friend:

Then she turned to me, let me see how angry she was, and that the anger was for me. She had been talking to herself, so what she said was a fragment of a much larger conversation. “You were just babies then!” she said.

“What?” I said.

“You were just babies in the war—like the ones up-stairs!”

I nodded that this was true. We had been foolish virgins in the war, right at the end of childhood.

“But you’re not going to write it that way, are you.” This wasn’t a question. It was an accusation.

“I—I don’t know,” I said.

“Well, I know,” she said. “You’ll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you’ll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men. And war will look just wonderful, so we’ll have a lot more of them. And they’ll be fought by babies like the babies upstairs.”

So then I understood. It was war that made her so angry. She didn’t want her babies or anybody else’s babies killed in wars. And she thought wars were partly encouraged by books and movies.

So I held up my right hand and I made her a promise: “Mary,” I said, “I don’t think this book of mine is ever going to be finished. I must have written five thousand pages by now, and thrown them all away. If I ever do finish it, though, I give you my word of honor: there won’t be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne.

“I tell you what,” I said, “I’ll call it ‘The Children’s Crusade.'”

She was my friend after that. (pp. 14-15)

I mean she’s right, there are many archetypes in war, and the media tends to favor the “strong” and “brave,” like the revenge-fueled ego-driven Paul Lazzaro and the cruel blood blood-hungry patriot Roland Weary.

However, this only adds to the realistic — and at times fatalistic — picture of war painted by Vonnegut.

Insofar as subtitling the novel The Children’s Crusade and having an elder veteran, a school teacher, point out that the war looks awfully like ‘The Children’s Crusade’:

Derby remained standing. “You seem older than the rest,” said the colonel.

Derby told him be was forty-five, which was two years older than the colonel. The colonel said that the other Americans had all shaved now, that Billy and Derby were the only two still with beards. And he said, “You know—we’ve had to imagine the war here, and we have imagined that it was being fought by aging men like ourselves. We had forgotten that wars were fought by babies. When I saw those freshly shaved faces, it was a shock. “’My God, my God—‘ I said to myself, ‘It’s the Children’s Crusade.’” (p. 106)

Also, this is my first time learning about the Dresden bombing and The Children’s Crusade. The comparison Vonnegut sustained between both events helped highlight that it’s the poor ‘babies’ that are being used as sacrificial weapons of mass destruction in the old man’s greed for domination.

History is truly harrowing. Oh, wait, we’re still living in harrowing times, my bad!

Vonnegut cleverly explains the difficulty of writing his novel about Dresden because, as we’re reminded multiple times, anti-war novels are challenging to write, and so is portraying the banalities with the horrors of war, whereas the typical romanticization of heroic and patriotic acts is expected:

It is so short and jumbled and jangled, Sam, because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre.

Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again. Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre, and it always is, except for the birds.

And what do the birds say? All there is to say about a massacre, things like “Poo-tee-weet?“

I have told my sons that they are not under any circumstances to take part in massacres, and that the news of massacres of enemies is not to fill them with satisfaction or glee.

I have also told them not to work for companies which make massacre machinery, and to express contempt for people who think we need machinery like that. (p. 19)

Writing this novel is Vonnegut’s way of putting the events at Dresden to rest. This novel reads as his moral obligation to present a personal yet fictionalized account to the collective consciousness of his time.

I looked through the Gideon Bible in my motel room for tales of great destruction. The sun was risen upon the Earth when Lot entered into Zo-ar, I read. Then the Lord rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of Heaven; and He overthrew those cities, and all the plain, and all the Inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground.

So it goes.

Those were vile people in both those cities, as is well known. The world was better off without them.

And Lot’s wife, of course, was told not to look back where all those people and their homes had been. But she did look back, and I love her for that, because it was so human.

So she was turned to a pillar of salt. So it goes.

People aren’t supposed to look back. I’m certainly not going to do it anymore.

I’ve finished my war book now. The next one I write is going to be fun.

This one is a failure, and had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt. It begins like this:

Listen:

Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.

It ends like this:

Poo-tee-weet? (pp. 21-22)

Once again, he is imparting the structure of his novel to his reader — we are presented with Billy Pilgrim’s story, a man stuck in time and who survived the massacre of Dresden, and confronted with the notion that life after war simply goes on. This is a complex look at the past as it is at once optimistic and defeatist approach with the bird chirping at the end.

Furthermore, the novel walks the tightrope of free will by exploring concepts of determinism, fatalism, and, at times, absurdism. This is apparent during Billy Pilgrim’s interactions with the Tralfamadorians:

“You sound to me as though you don’t believe in free will,” said Billy Pilgrim.

“If I hadn’t spent so much time studying Earthlings,” said the Tralfamadorian, “I wouldn’t have any idea what was meant by ‘free will.’ I’ve visited thirty-one inhabited planets in the universe, and I have studied reports on one hundred more. Only on Earth is there any talk of free will.” (p. 86)

Whereas humans are concerned with free will, right and wrong, and the meaning of life, it seems that the Tralfamadorians are above our limited Earthling consciousness, prevailing in a state of absurdist-like peace. Funnily enough, Kilgore Trout, the author that Rosewater [Billy’s PTSD roomie at the veterans hospital] introduced him to, taps into this higher consciousness through his science fiction novels:

“Maybe he was working too hard,” said Rosewater, He held a book he wanted to read, but he was much too polite to read and talk, too, easy as it was to give Billy’s mother satisfactory answers. The book was Maniacs in the Fourth Dimension, by Kilgore Trout.

It was about people whose mental diseases couldn’t be treated because the causes of the diseases were all in the fourth dimension, and three dimensional Earthling doctors couldn’t see those causes at all, or even imagine them.

One thing Trout said that Rosewater liked very much was that there really were vampires and were wolves and goblins and angels and so on, but that they were in the fourth dimension. So was William Blake, Rosewater’s favorite poet, according to Trout.

So were heaven and hell. (p. 104)

We can see the influence of the Trafalmadorians as most paragraphs end with the sayings ‘so it goes’ and ‘and so on’ after witnessing death or destruction, which is a fatalistic approach, reinforcing the meaninglessness and desensitization of war. For me, it also reads as dark humor, cutting tension.

PTSD and the Will To Live

We explore more of this absurd meaninglessness during Billy’s stay at the veterans’ hospital:

Rosewater said an interesting thing to Billy one time about a book that wasn’t science fiction. He said that everything there was to know about life was in The Brothers Karamazov, by Feodor Dostoevsky. “But that Isn’t enough any more,” said Rosewater.

Another time Billy heard Rosewater say to a psychiatrist, “I think you guys are going to have to come up with a lot of wonderful new lies, or people just aren’t going to want to go on living.” (p. 101)

Absurd to contrast the events of the war with the superficiality of America and the American dream to get rich. Billy’s mom comes to visit him at the veterans’ hospital. Meanwhile, all she cares about is that shellshocked son is going to be ‘engaged to a very rich girl’ (p. 104)

He changed the subject now, congratulated Valencia on her engagement ring.

“Thank you,” she said, and held it out so Rosewater could get a close look. “Billy got that diamond in the war.”

“That’s the attractive thing about war,” said Rosewater. “Absolutely everybody gets a little something.” (pp. 110-111)

The previous passage is even more disconcerting, since we know that everything in war has a cost, usually at the expense of someone else’s misfortune. Not everyone is lucky in looting during wartime. The kind elderly school teacher Derby gets shot for taking a teacup after surviving the bombing.

What’s even more harrowing is the anecdote Vonnegut shared at the opening of the novel. If you recall: “All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his.” (p. 1)

Hence, Derby was real and was shot for taking a teacup, which he probably wanted to bring back to his wife.

Well, what did we expect? We got an anti-war novel all right.

Twisted Collective Memory, An Erased History

And now we are coming back full circle: the propaganda of sensationalizing war, when in reality the young die for the greed of the old, and then what truly happened is erased or overlooked from collective memory.

Even then I was supposedly writing a book about Dresden. It wasn’t a famous air raid back then in America. Not many Americans knew how much worse it had been than Hiroshima, for instance. I didn’t know that, either. There hadn’t been much publicity I happened to tell a University of Chicago professor at a cocktail party about the raid as I had seen it, about the book I would write. He was a member of a thing called The Committee on Social Thought. And he told me about the concentration camps, and about how the Germans had made soap and candles out of the fat of dead Jews and so on.

All I could say was, “I know, I know. I know.” (p. 10)

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve never heard about the Dresden bombing before. I wonder how many others, all of these decades later, learn about this event by reading this fictionalized account?

“Americans have finally heard about Dresden,” said Rumfoord, twenty-three years after the raid. “A lot of them know now how much worse it was than Hiroshima. So I’ve got to put something about it in my book. From the official Air Force standpoint, it’ll all be new.”

“Why would they keep it a secret so long?” said Lily.

“For fear that a lot of bleeding hearts,” said Rumfoord, “might not think it was such a wonderful thing to do.”

It was now that Billy Pilgrim spoke up intelligently.

“I was there,” he said. (p. 191)

Once again, in the previous passage, we see how people who haven’t been to the war are quick to defend war crimes and justify its horrors by painting it in an unrealistic light. Hence why Rumfoord ignores Billy, to ignore Billy is to stay ignorant and righteous. But here he is and here is Vonnegut’s account too, like Billy says, ‘I was there.’

Those three little words, in my opinion, are the most powerful words in the novel besides ‘The Children’s Crusade.’ This is further proven because one of Vonnegut’s only authorial interjections while crafting Billy Pilgrim’s narrative states, ‘I was there. So was my old war buddy, Bernard V. O’Hare.’ (p. 67)

There in the hospital, Billy was having an adventure very common among people without power in time of war: He was trying to prove to a willfully deaf and blind enemy that he was interesting to hear and see.

He kept silent until the lights went out at night, and then, when there had been a long period of silence containing nothing to echo, he said to Rumfoord, “I was in Dresden when it was bombed. I was a prisoner of war.”

Rumfoord sighed impatiently.

“Word of honor,” said Billy Pilgrim. “Do you believe me?”

“Must we talk about it now?” said Rumfoord. He had heard. He didn’t believe.

“We don’t ever have to talk about it,” said Billy.

“I just want you to know: I was there.” (p. 193)

Here are my parting thoughts I have about the narrative frame and the overall story. Quite a few times, we understand that Kilgore Trout writes about the Trafalmadorians, which can be interpreted as Billy’s psychological projection of being abducted while experiencing PTSD.

Compare the following two passages:

So Rosewater told him. It was The Gospel from Outer Space, by Kilgore Trout. It was about a visitor from outer space, shaped very much like a Tralfamadorian, by the way. The visitor from outer space made a serious study of Christianity, to learn, if he could, why Christians found it so easy to be cruel. He concluded that at least part of the trouble was slipshod storytelling in the New Testament. He supposed that the intent of the Gospels was to teach people, among other things, to be merciful, even to the lowest of the low.

But the Gospels actually taught this:

Before you kill somebody, make absolutely sure he isn’t well connected. So it goes. (pp. 108-109)

But Billy Pilgrim wasn’t beguiled by the back of the store. He was thrilled by the Kilgore Trout novels in the front. The titles were all new to him, or he thought they were. Now he opened one. It seemed all right for him to do that. Everybody else in the store was pawing things. The name of the book was The Big Board. He got a few paragraphs into it, and then he realized that he had read it before—years ago, in the veterans’ hospital. It was about an Earthling man and woman who were kidnapped by extra-terrestrials. They were put on display in a zoo on a planet called Zircon-212. (p. 201)

Furthermore, the second nugget-like clue that could prove this is knowing that Vonnegut is crafting these frames to demonstrate the absurdity of war and the impossibility of peace on Earth since the Trafalmadorians admit to Billy that they explode the world accidentally like a bad Oppenheimer experiment gone wrong, which links back to bombings like Dresden, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, etc.

Either way, Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five” offers a lot to unpack, think about, and revisit. I highly recommend the book to everyone who hasn’t read it yet. It’s one of my new favourite classics. It is rich, poignant, memorable, and existentially philosophical.

Here is a fun piece of trivia I learned while reading the novel’s Wikipedia page:

In 1970, Slaughterhouse-Five was nominated for best-novel Nebula and Hugo Awards. It lost both to The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin.

I think about my education sometimes. I went to the University of Chicago for a while after the Second World War. I was a student in the Department of Anthropology. At that time, they were teaching that there was absolutely no difference between anybody.

They may be teaching that still.

Another thing they taught was that nobody was ridiculous or bad or disgusting. Shortly before my father died, he said to me, “You know—you never wrote a story with a villain in it.”

I told him that was one of the things I learned in college after the war. (p. 8)

Beds are places of rest, safety, security, but only if your sleep is peaceful. For insomniacs, the bed is a cruel tormentor; for those of us with parasomnias, the bed is a haunted crypt. (p. 18)

Sleep paralysis was once interpreted as being ‘ridden’ by the incubus or succubus, a shadowy, impish figure that sought to squeeze the life out of its helpless victim. (p. 20)

EVERYTHING WAS BEAUTIFUL AND NOTHING HURT. (p. 122)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply