This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

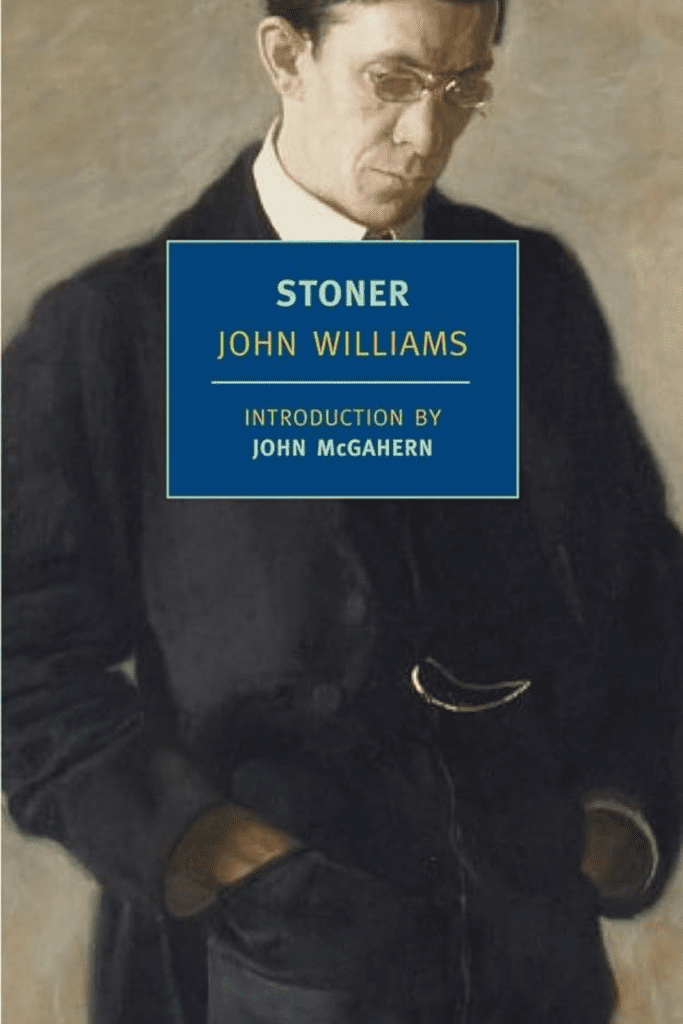

“Stoner” is a literary fiction novel, set at the end of the 19th century, that follows William Stoner’s life, a poor son of a Missouri farmer turned university scholar.

- Date finished: January 11th, 2024

- Pages: 292

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Novel

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Fiction | Literature | Classics

Buy “Stoner”

As mentioned, “Stoner” depicts the quiet but rich inner life of a university student, then professor, named William Stoner.

“Stoner” is both a glass half-full and half-empty type of book. At times, it’s quite a depressing read. Yet, it remains impactful and poignant. I have felt frustrated all while nodding appreciatively along when reading about the main character William Stoner’s life. He is the epitome of a little life. A quiet life. An insignificant yet significant life.

In a way, it is up to the reader to look at Stoner’s life with pity or with awe, maybe both.

Apathy – a lack of passion – can destroy one’s life. In Stoner’s life, only literature has saved him and given him his purpose of being.

Be warned, if you’re an academic or an alumni, this will fill you with nostalgia. This book, in part, is for people who love academia and for those who immerse themselves deeply in literature as a form of being.

When he was much older, he was to look back upon his last two undergraduate years as if they were an unreal time that belonged to someone else, a time that passed, not in the regular flow to which he was used, but in fits and starts. p. 14

Nostalgia is a central theme that wraps around the narrative until the very last page. The things we latch onto have a sneaky way of changing us, e.g., when Stoner first attends university and the influence of his long-dead professor Archer Sloane who becomes a foreshadowing of Stoner’s life (p. 14.) Some professors tend to recognize and nurture pupils more akin to them, reminding them of their old selves:

“But don’t you know, Mr. Stoner?” Sloane asked. “Don’t you understand about yourself yet? You’re going to be a teacher.” Suddenly Sloane seemed very distant, and the walls of the office receded. Stoner felt himself suspended in the wide air, and he heard his voice ask, “Are you sure?”

“I’m sure,” Sloane said softly.

“How can you tell? How can you be sure?”

“It’s love, Mr. Stoner,” Sloane said cheerfully. “You are in love. It’s as simple as that.” p. 20

Furthermore, the novel raises some interesting questions surrounding the necessity of Academia.

Is Academia a way of avoiding the world? (p. 19) What happens when you devote yourself and your whole livelihood to a subject you were told you are well suited for? (p. 20)

Personally, I am constantly in a state of critiquing and missing university. It is no great wonder that fictional academia (Dark Academia/Campus Novel) is a subgenre of its own.

In my own personal journey, I have clung to my degrees. I was influenced by well-meaning and encouraging professors to pursue a Master’s Degree in French Literature. Between the walls of Academia, between the pages of the books I’ve read, underlined, and dreamt about, I was safe, I was heard. It is a cocoon. No need to go out into the world. In those years, I would have stopped and elongated time regardless of the price. And since (at the time of writing it’s only been four years since graduating) I feel my inadequacy and my inability to let it go. Letting the experience go.

Let us consider Dave Masters’s view on University:

“It [the university] is an asylum or—what do they call them now?—a rest home, for the infirm, the aged, the discontent, and the otherwise incompetent. Look at the three of us we are the University. The stranger would not know that we have so much in common, but we know, don’t we? We know well.” p. 30

Whether it is a harsh or exaggerated observation, I can’t help but feel like his statement carries some gravity. If it weren’t so, Stoner wouldn’t think of Dave Masters as often as he does in his lifetime. I mean sure they were good friends for those 2 undergraduate years but he lost his life a longtime ago in the War. He lost his life for the ideas and freedom that we keep locked behind the University’s expensive, leaden doors.

“It’s for us that the University exists, for the dispossessed of the world; not for the students, not for the selfless pursuit of knowledge, not for any of the reasons that you hear.” p. 31

We equally come to understand that despite all of his years of teaching, and being involved in literature, Stoner is reduced by his inability to bridge the gap for his appreciation. There remains a gulf between his impressions and his teachings. He reflects:

He was ready to admit to himself that he had not been a good teacher. Always, from the time he had fumbled through his first classes of freshman English, he had been aware of the gulf that lay between what he felt for his subject and what he delivered in the classroom. He had hoped that time and experience would repair the gulf; but they had not done so. Those things that he held most deeply were most profoundly betrayed when he spoke of them to his classes; what was most alive withered in his words; and what moved him most became cold in its utterance. And the consciousness of his inadequacy distressed him so greatly that the sense of it grew habitual, as much a part of him as the stoop of his shoulders. p. 112

We remember how humane Stoner is. Pity and awe. Apathy and passion. The moments of passion he experiences are mostly related to Literature and Teaching with some reservations towards his wife-antagonist Edith, his dejected daughter Grace, and his brief affair with his student Katherine.

And then it comes. At the end of his life, he repeats to himself, “What did you expect?” Both with acceptance, regret, and humility. Many live life this way. No need to be a literature teacher to experience this dispossession.

“What did you expect?” (p. 277) becomes the final blow, the final apathetic resignation of Stoner’s life.

You can also watch my reading vlog where I discuss both “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” and “Stoner”:

Sometimes, immersed in his books, there would come to him the awareness of all that he did not know, of all that he had not read; and the serenity for which he labored was shattered as he realized the little time he had in life to read so much, to learn what he had to know.

The love of literature, of language, of the mystery of the mind and heart showing themselves in the minute, strange, and unexpected combinations of letters and words, in the blackest and coldest print-the love which he had hidden as if it were illicit and dangerous, he began to display, tentatively at first, and then boldly, and then proudly. p. 113

During that year, and especially in the winter months, he found himself returning more and more frequently to such a state of unreality; at will, he seemed able to remove his consciousness from the body that contained it, and he observed himself as if he were an oddly familiar stranger doing the oddly familiar things that he had to do. It was a dissociation that he had never felt before; he knew that he ought to be troubled by it, but he was numb, and he could not convince himself that it mattered. He was forty-two years old, and he could see nothing before him that he wished to enjoy and little behind him that he cared to remember. p. 181

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply