This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

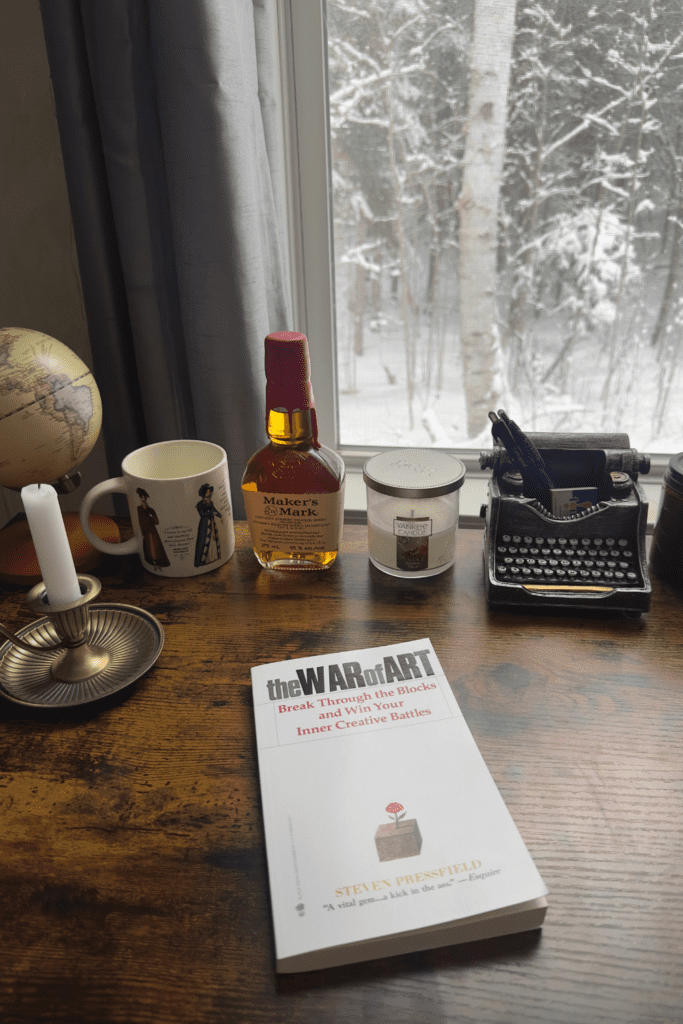

“The War of Art” is a short but punchy non-fiction book that aims to help you break through your creative blocks and win your inner creative battles.

- Date finished: January 17th, 2025

- Pages: 165

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Non-Fiction

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Non-Fiction | Writing | Self-Help

Buy “The War of Art”

As mentioned above, “The War of Art” is the ideal push for creatives that are procrastinating, postponing, and stuck in their creative pursuits.

Did I expect “The War of Art” to change my life? Yup! And that was my bad.

By no means is this book bad, I had too high hopes. You know those books you save for rainy days or for when you’re desperate to fix your life? Well, this was one of them. I wanted to get back into novel writing with full force this year…!

This book underwhelmed me because I’ve read similar “ideas” in Julia Cameron’s works, notably in her book “Walking in This World” while writing my morning pages and working through The Complete Artist’s Way.

Evidently, I do believe that Pressfield knack for labeling everything that gets in the way of our creative work as ‘resistance’ is simplistic. Yet the author had a message and he stood by it to the very end. For that, I can admire his tenacity.

I will admit though “The War of Art” has resonated with me in later weeks when I think about ‘resistance’ in doing the work I want to do. For example, this review was written a month and a half after I finished reading this book even though I swore to myself this year (the year 2025) that I will no longer delay writing my book reviews. Funny how resistance works.

Another example that proved itself to me is the one of RESISTANCE AND SELF-DRAMATIZATION in which he talks about how resistance is Santa Claus’s evil twin, making its rounds in different households.

Enough about my own life, here are some of my favorite passages instead:

RESISTANCE AND SELF-DRAMATIZATION

Creating soap opera in our lives is a symptom of Resistance. Why put in years of work designing a new software interface when you can get just as much attention by bringing home a boyfriend with a prison record?

Sometimes entire families participate unconsciously in a culture of self-dramatization. The kids fuel the tanks, the grown-ups arm the phasers, the whole starship lurches from one spine-tingling episode to another. And the crew knows how to keep it going. If the level of drama drops below a certain threshold, someone jumps in to amp it up. Dad gets drunk, Mom gets sick, Janie shows up for church with an Oakland Raiders tattoo. It’s more fun than a movie. And it works: Nobody gets a damn thing done.

Sometimes I think of Resistance as a sort of evil twin to Santa Claus, who makes his rounds house-to-house, making sure that everything’s taken care of. When he comes to a house that’s hooked on self-dramatization, his ruddy cheeks glow and he giddy-ups away behind his eight tiny reindeer.

He knows there’ll be no work done in that house. (p. 25)

RESISTANCE AND PROCRASTINATION

Procrastination is the most common manifestation of Resistance because it’s the easiest to rationalize.

We don’t tell ourselves, “I’m never going to write my symphony.” Instead we say, “I am going to write my symphony; I’m just going to start tomorrow.” (p. 21)

RESISTANCE AND PROCRASTINATION, PART TWO

The most pernicious aspect of procrastination is that it can become a habit. We don’t just put off our lives

today; we put them off till our deathbed.

Never forget: This very moment, we can change our lives.

There never was a moment, and never will be, when we are without the power to alter our destiny. This second, we can turn the tables on Resistance.

This second, we can sit down and do our work. (p. 22)

RESISTANCE AND FUNDAMENTALISM

The fundamentalist (or, more accurately, the beleaguered individual who comes to embrace fundamentalism) cannot stand freedom. He cannot find his way into the future, so he retreats to the past. He returns in imagination to the glory days of his race and seeks to reconstitute both them and himself in their purer, more virtuous light. He gets back to basics. To fundamentals.

Fundamentalism and art are mutually exclusive. There is no such thing as fundamentalist art. This does not mean that the fundamentalist is not creative. Rather, his creativity is inverted. He creates destruction. Even the structures he builds, his schools and networks of organization, are dedicated to annihilation, of his enemies and of himself. (p. 35)

To combat the call of sin, i.e., Resistance, the fundamentalist plunges either into action or into the study of sacred texts. He loses himself in these, much as the artist does in the process of creation. The difference is that while the one looks forward, hoping to create a better world, the other looks backward, seeking to return to a purer world from which he and all have fallen.

The humanist believes that humankind, as individuals, is called upon to co-create the world with God.

This is why he values human life so highly. In his view, things do progress, life does evolve; each individual has value, at least potentially, in advancing this cause.

The fundamentalist cannot conceive of this. In his society, dissent is not just crime but apostasy; it is heresy, transgression against God Himself.

When fundamentalism wins, the world enters a dark age. (p. 36)

RESISTANCE AND SELF-DOUBT

Self-doubt can be an ally. This is because it serves as San indicator of aspiration. It reflects love, love of something we dream of doing, and desire, desire to do it. If you find yourself asking yourself (and your friends), “Am I really a writer? Am I really an artist?” chances are you are.

The counterfeit innovator is wildly self-confident.

The real one is scared to death. (p. 39)

Are you paralyzed with fear? That’s a good sign.

Fear is good. Like self-doubt, fear is an indicator. Fear tells us what we have to do.

Remember our rule of thumb: The more scared we are of a work or calling, the more sure we can be that we have to do it.

Resistance is experienced as fear; the degree of fear equates to the strength of Resistance. Therefore the more fear we feel about a specific enterprise, the more certain we can be that that enterprise is important to us and to the growth of our soul. That’s why we feel so much Resistance.

If it meant nothing to us, there’d be no Resistance.

Have you ever watched Inside the Actors Studio?

The host, James Lipton, invariably asks his guests, “What factors make you decide to take a particular role?” The actor always answers: “Because I’m afraid of it.”

The professional tackles the project that will make him stretch. He takes on the assignment that will bear him into uncharted waters, compel him to explore unconscious parts of himself. (p. 40)

PROFESSIONALS AND AMATEURS

Aspiring artists defeated by Resistance share one trait. They all think like amateurs. They have not yet turned pro.

The moment an artist turns pro is as epochal as the birth of his first child. With one stroke, everything changes. I can state absolutely that the term of my life can be divided into two parts: before turning pro, and after.

To be clear: When I say professional, I don’t mean doctors and lawyers, those of “the professions.” I mean the Professional as an ideal. The professional in contrast to the amateur. Consider the differences.

The amateur plays for fun. The professional plays for keeps.

To the amateur, the game is his avocation. To the pro it’s his vocation.

The amateur plays part-time, the professional full-time.

The amateur is a weekend warrior. The professional is there seven days a week.

The word amateur comes from the Latin root meaning “to love.” The conventional interpretation is that the amateur pursues his calling out of love, while the pro does it for money. Not the way I see it. In my view, the amateur does not love the game enough. If he did, he would not pursue it as a sideline, distinct from his “real” vocation.

The professional loves it so much he dedicates his life to it.

He commits full-time.

That’s what I mean when I say turning pro.

Resistance hates it when we turn pro. (pp. 62-63)

A PROFESSIONAL

Someone once asked Somerset Maugham if he wrote on.

schedule or only when struck by inspiration. “I write only when inspiration strikes,” he replied. “Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o’clock sharp.”

That’s a pro.

In terms of Resistance, Maugham was saying, “I despise Resistance; I will not let it faze me; I will sit down and do my work.”

Maugham reckoned another, deeper truth: that by performing the mundane physical act of sitting down and starting to work, he set in motion a mysterious but infallible sequence of events that would produce inspiration, as surely as if the goddess had synchronized her watch with his.

He knew if he built it, she would come. (p. 64)

⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply