This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

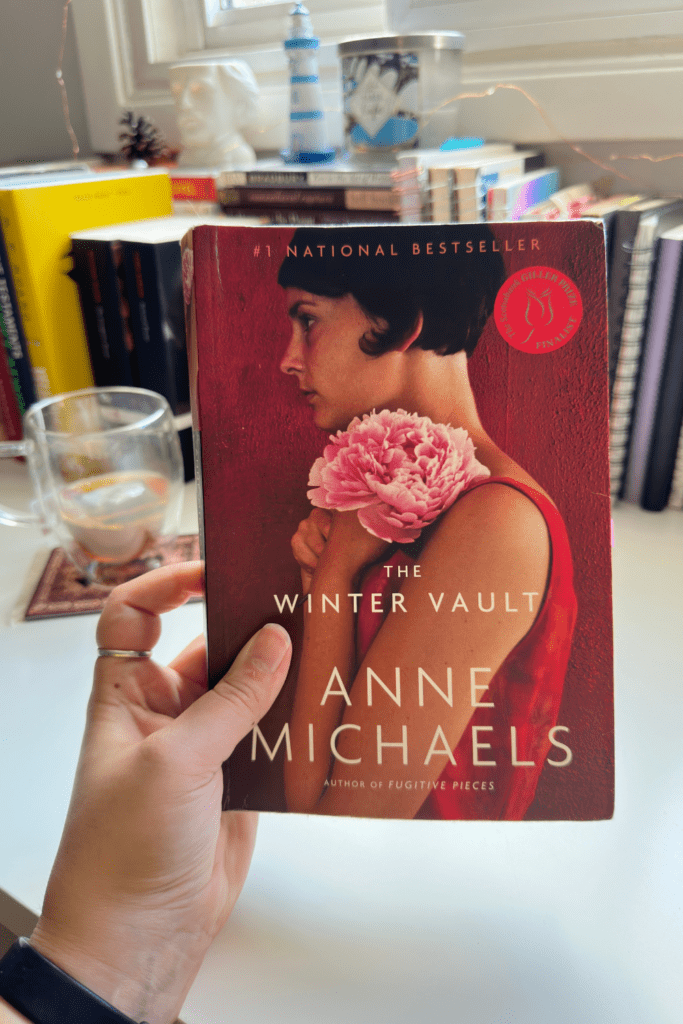

“The Winter Vault” is the second historical fiction novel by the bestselling Canadian author Anne Michaels.

- Date finished: September 4th, 2024

- Pages: 252

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Novel

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Literary Fiction | Historical Fiction | Canadian Literature

“The Winter Vault” is an expansive book of love, displacement, and grief, written in Anne Michaels’s distinctive poetic style. It is a dual-timeline historical novel, following a young grieving couple and their time spent in Canada (during the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway) and Egypt (during the building of the Aswam dam.)

In “The Winter Vault,” Anne Michaels weaves a beautiful tapestry, creating a bridge between what becomes of one’s life: love, loss, memory, ancestry, history (oral, art, archeological, etc.), grief, and love again.

One can always count on Anne Michaels’ historical collision course intersecting personal with collective tragedy, the past being defined and polished by the present.

We can witness this enmeshing simply by the opening lines:

“Perhaps we painted on our own skin, with ochre and char-coal, long before we painted on stone. In any case, forty thousand years ago, we left painted handprints on the cave walls of Lascaux, Ardennes, Chauvet.”

The story follows the grandiose project of carefully and expertly erecting, to conserve and save, Abu Simbel temples and other Nubian monuments in Egypt.

This project is carefully juxtaposed with another previous project – the drowning of the villages around the St Lawrence for the St. Lawrence Seaway in Canada. Inhabitants and their houses were to be moved, and so were their gravesites.

This constant blend between fact and fiction invites the reader to care and extract truths from the fictions at hand carefully. In some way, I have found myself on these little quests, researching Nubian customs, the structure of the temples, the explorer Giovanni Belzoni, and the St. Lawrence Dam.

But now let’s visit the two main characters, Avery Escher and Jean Shaw:

Two lives intersect. Avery, an engineer, meets Jean, a botanist, during the St. Lawrence Seaway project. They are both troubled and intentional in conserving what is now lost. Jean keeps records of plants after her parents’ passing and Avery works on the projects he was supposed to work on with his recently deceased British father. Both are grieving and lonely. And so, they find each other.

These intimate moments between Avery and Jean make me believe in true intimate, long-lasting love. She shares her knowledge of plants and botany with him, while he shares his knowledge about buildings and architectural structures. And together, they create this beautiful enmeshment:

“It was an engagement of mind that was almost shattering in its pleasure.” (p. 81)

Upon meeting, Jean is passionate about keeping records, collecting data, and saving memories’ of the St. Lawrence landscape. Therefore, Jean keeps a record of the plants on the sites that are about to be flooded. This catches Avery’s eyes, prompting him to ask what she’s doing:

“I’m keeping a record, she said bitterly. I’m going to transplant these particular plants, this particular generation. Though of course they’ll never grow and reproduce themselves exactly as they would have, if they’d been left alone.” (p. 50)

At large, these small acts display a greater, more somber picture as we’ll learn later when it comes to the necessity of preserving by the act of sharing memories when Jean meets Polish artist Lucjan who also conserves his memories of displacement and grief post-WWII. As we come to understand it, not everything that is destroyed is lost due to memory. And yet still, reconstruction and displacement leave an unmistakable trail of loss and destruction. For example, there’s the issue of the gravesites along the St. Lawrence that have been flooded and are to be moved into the new towns. An elderly lady proclaims the following to Avery:

“Can you move what was consecrated?

Can you move that exact empty place in the earth I was to lie next to him for eternity? It’s the loneliness of eternity I’m talking about! Can you move all those things?” (p. 47)

As I mentioned, the narrative is primarily about grief, loss, and displacement. In a way, we watch Avery and Jean go through this displacement when they lose their parental figures and later when Jean gives birth to their stillborn baby girl in Egypt.

“We do not like to think about children’s fears, Marina had said one afternoon in the weeks alone with Jean. We push them aside to concentrate on their innocence. But children are close to grief, they are closer to grief than we are. They feel it, undiluted, and then gradually they grow away from that flesh-knowledge. They know all about the terror of the woods, the witch-mother, things buried and not seen again.

In every child’s fear is always the fear of the worst thing, the loss of the person they love most.” (p. 162)

This displacement and let’s name it relocation of grief is put plainly after the completion of Avery’s project at Abu Simbel, in which he’s unsure if the displacement of all of those people and the erecting of the temples, has the project succeeded in doing, once again, more harm than good. If there’s any consolation to be had at all:

“Every action has a cause and a consequence …

I do not believe home is where we’re born, or the place we grew up, not a birthright or an inheritance, not a name, or blood or country. It is not even the soft part that hurts when touched, that defines our loneliness the way a bowl defines water. It will not be located in a smell or a taste or a talisman or a word …

Home is our first real mistake. It is the one error that changes everything, the one lesson you could let destroy you. It is from this moment that we begin to build our home in the world. It is this place that we furnish with smell, taste, a talisman, a name.” (p. 183)

Multiple times in this novel we see water as this double force. The first is water as destruction caused by the dams; flooding, uprootedness, and displacement. But then, we are also met with water as renewal, healing, and nourishment for the soil to grow plants, bringing in new life, and washing away grief. We can see this unravel in the closing lines once Jean and Avery make their way back to each other after their own personal tragedy:

“Regret is not the end of the story; it is the middle of the story.

When Jean was done, she knew how careful she had to be. Not to erase, but to wash away.” (p. 336)

“We become ourselves when things are given to us or when things are taken away.” (p. 94)

“To mourn is to honour. Not to surrender to this keening, to this absence — a dishonouring.” (p. 248)

“There is no need to replace your grieving with penance.” (p. 249)

“In every childhood there is a door that closes. Only real love waits while we journey through our grief. That is the real trustworthiness between people. In all the epics, in all the stories that have lasted through many lifetimes, it is always the same truth: love must wait for wounds to heal. It is this waiting we must do for each other, not with a sense of mercy, or in judgment, but as if forgiveness were a rendezvous. How many are willing to wait for another in this way?” (pp. 93-94)

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply