This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

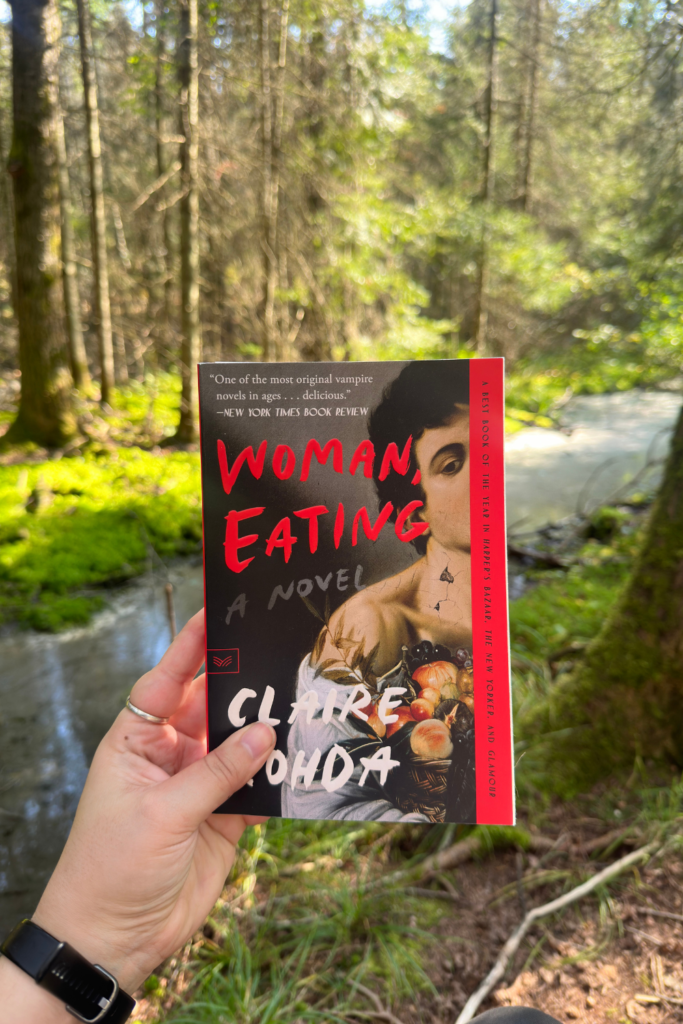

“Woman, Eating“ follows a 23-year-old vampire starting her art internship and living independently from her mother for the first time.

- Date finished: September 15th, 2024

- Pages: 240

- Format: Paperback

- Form: Novel

- Language read: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Horror | Literary Fiction | Vampires

Buy “Woman, Eating“

“Woman, Eating“ follows 23-year-old vampire Lydia. She’s hungry, lost, and depressed, but most importantly, she’s starting her adult life: falling in love, moving away from her mother, and starting an art internship.

“Woman, Eating“ is not your typical vampire novel. It’s insanely human and tender to its core. The more I sit with my reflections on this book, I’ve come to realize that it’s not immortality that the main character (Lydia, an immortal vampire) struggles with, not really, it’s living. As readers, we watch as a 23-year-old Lydia unpacks her mother’s shame-based conditioning and sets out for the first time in the adult world—some really scary stuff if you ask me.

A depressed, anxious, lonely, moody person, Lydia as a main character is painfully as relatable as it gets for me:

“Whenever there is something planned in my life-either meeting a friend, going on a school or uni trip, going for a walk, or, like today, starting an internship —when it actually comes to the day I have to go through with the plan, it goes from being something I’m excited about to something I dread. If I arrange to go to the cinema in a week’s time, for instance, when the time to go comes around, it becomes the last thing I want to do. My instinct, always, is to stay in. Right now, I don’t want to go to the Otter, even though I’ve planned the route meticulously in my mind, and feel prepared. I want to stay here on my concrete floor and look at the ceiling. I definitely don’t want to meet people.

The idea of it, from the perspective of where I am now, alone in this room, is strange and feels completely unnatural.” (p. 41)

In essence, this book reads as a deep character study. Like many depressed, self-aware with chronic low self-esteem people, it’s a pleasure to read Lydia’s thoughts and watch as she tries to bridge this gap into adulthood and accept herself for who she is:

“I don’t know what it is. It’s not that I don’t value myself, which I’m sure is what a psychologist would say is the case. It’s more that I know that I can survive for ages without eating, and pushing my body in the vague direction of its limits is satisfying, in that I feel more alive than I ever otherwise do. I’ve heard of people who go running for something like fifty or sixty miles across the countryside-and not just the flat countryside in Kent, but the hilly countryside up near Sheffield-just so they can feel the same feeling. It’s as though, because they are pushing their bodies to their outermost limits, they can feel their mortality. Like, they go right up to the edge of what it means to be alive, and look over it and down at the huge, immeasurable void below, and feel joy because they’re not in the void, but above it. That’s what being alive is. But, normally, people don’t see over the edge and witness the contrast between the everythingness of life and the nothingness of death, so they don’t feel or understand that life is exhilarating, like those runners do.” (p. 17)

Another central theme of this novel is hunger. True, it reads like an anorexic’s diary (I would know.) At the root, though, depriving herself of food stems from her mother’s shame of being a vampire, being “impure.”

“Sometimes, I feel disgust when I watch people eating food; other times, I feel envy. I’d like to be able to try and taste everything, to understand all human experience through food.” (p. 66)

Similar to anorexics, abstaining from food becomes an obsession and also a way to self-punish and gain control. This disordered eating is traditionally passed from mothers to daughters. In the case of the novel, being a vampire exacerbates this societal conditioning:

“We only ever got pig blood. This wasn’t because it was the only type of animal blood the butcher had. “Pigs are dirty, my mum said once. “It’s what your body deserves.” But it turns out that pigs aren’t naturally dirty. Rather, humans keep pigs in dirty conditions, feeding them rotten vegetables, letting the mud in their too-small pens mix with their feces; the filth of the pig is just symptomatic of the sins of the human. Wild pigs eat plants.

They’ve even been shown to clean fruit in creeks before eating it, and they never eat or roll around in their own feces. I told my mum this, but she was adamant that the pig was the filthiest animal and was what we deserved. It was what I grew up eating, never touching anything else—just thinking, dreaming, imagining the taste of other blood.” (p. 36)

Lydia goes as far as watching YouTube videos of WEIAD (What I Eat in a Day) by different influencers – models, students, Japanese, etc. Let me just say, I’ve been guilty of doing this for over a decade while in and out of eating disorder recovery. This was painfully relatable. She discusses these videos in a way that is so human and realistic. For many people, food is a constant struggle, noise, and a way to reward/punish/nourish:

“I don’t know what it is about these videos that I find so soothing. Sometimes, I tell myself that my watching them is an anthropological experiment, something I do to better understand full humans, or perhaps my own human side. I suppose food is a part of life that most humans can control. They give food a lot of power — food can make a person more beautiful, or less beautiful; it can improve or damage skin; it can make a person’s body more attractive, help make hair and nails stronger; it can heal you, or slowly kill you. There’s also clean food and dirty food; if you eat clean, the message is that you are a clean and pure per-son; if you eat dirty, then the message is that you are dirty and impure. If you lose control in your life, you can find control in your food. This video by Mina has the feeling of an educational video. Lots of them take that tone, as though their message is: if you eat like me, you will become me.” (p. 65)

Back to the coming-of-age theme of this novel…

Going into adulthood, once we’re alone or independent, we can finally work through what we were taught, and in some cases shamed by our parental figure(s). Lydia is an extreme case as she’s extremely codependent on her mother. Her mother is hardly in the picture in this novel but she shows up on every page. Thankfully, Lydia comes to these realizations.

“I realized that “demon” is a subjective term, and the splitting of my identity between devil and God, between impure and pure, was something that my mum did to me, rather than the reality of my existence. Still, though, after a lifetime of eating just pig blood, I feared eating anything else, especially human, in case I developed a taste for it, and then an addiction. Instead of trying different bloods, I tried starvation, feeling out the divide not between the demon and human inside me but between life and death.” (p. 90)

“I want to be a good person. Lots of people realize that they do too, I think, when they have to live as adults for the first time.

They see people with less than them and they have a realization that the main thing they want in life isn’t necessarily to be rich or successful, but to be good. I don’t think my mum’s decision to not drink human blood, and to raise me so I didn’t either, comes from a desire to be good, though. It has always been an expression of her lack of self-worth. She always said that she didn’t deserve things; she didn’t deserve to feel satiated, to try the blood of a nobler animal than the pig, such as the horse, even the cow; she didn’t deserve happiness; she didn’t deserve me either, and I in turn didn’t deserve the horse or cow or happiness because of what was in me that she had passed down from her body to mine.

“We shouldn’t ever give the devil more than enough to survive, she once said. “And that is what the demon in us is. We eat only to keep the human alive,” she said, because to deny the human side sustenance was to commit it to death, and that would be a worse sin than our continued existence was. I want to be good, though. I don’t know for sure where this desire comes from—perhaps from my dad, whose life and person must be preserved somewhere inside me.” (pp. 57-58)

What’s even more fascinating when it comes to Lydia’s need to reconcile her human with her demon sides is that she’s also biracial – her father is Japanese and her mother is Thai while Lydia is raised in London. In many ways, she’s an outsider. (I’m also biracial and living in Canada with my immigrant parents.) Therefore, Lydia also takes after her deceased father whom she’s never met by being part-human, and interested in the arts (as he was a famous Japanese painter.)

Overall, this book was so incredibly tender. I’ve focused on the eating disorder and her codependent shame-based relationship with her mother—but this book is also about love, art, self-advocacy, self-discovery, and male abuse of power.

“I think I have known for a while that neither side of me can be separated from the other, and that this is true of my mum too; that I can’t punish the demon by making it eat only pig blood without punishing the human; I can’t listen to just one side, and block out the other; I can’t force one side to be dormant while I live a life pretending to only be the other side; I can’t starve either side out of myself. Really, I don’t even have “sides” at all. I’m two things that have become one thing that is neither demon nor human.” (p. 219)

“So, are you an artist as well?” I ask, trying to make conversation. But when I turn around to look at him, he just shakes his head and then says, “You?”

“Yes,” I say. I feel a bit guilty saying this, though, since I haven’t actually made any work since I graduated. I haven’t really been doing much of anything since I graduated. I feel like, in the year after college that I spent at home with my mum, worrying about her, trying to keep her safe, I didn’t really live; I essentially took a break from my life to focus on my mum’s life. Currently, I’m hoping-to-be rather than being—I’m not yet an independent adult; I’m hoping to become one. I’m not yet an artist; I’m hoping to become one.” (p. 47)

“When I was maybe nine or ten, my mum told me that turning me was the biggest sacrifice she had ever made, “because I didn’t know whether you’d grow up still or if you’d just be stuck as a baby forever, stuck as my responsibility forever.” But now I wonder whether she somehow knew all along that I would continue growing and whether she had just said that to make me feel indebted to her. And if that was the case, it worked. It excused her behavior. Her madness and her fluctuating moods, her self-hatred, while I was growing up. Everything in me that makes me anxious moving forward in life, that makes me feel as though I’m doing things wrong, that I’m not on the right path some-how, that I’m bad in some way, comes from her, and yet I’ve always forgiven her. She once told me that while she was pregnant she worried that I would come out full demon—-basically, just a shadow with eyes that engulfed people and drained them of all their humanity. When she told me that, I expected her to follow it up with a sentence beginning, “But, you were …” or “But, I shouldn’t have worried,” but she didn’t. Now I wonder if I’ve been useful to her only as something she can pour everything she despises about herself into, something that she could raise to hate itself so that she’d have company in her feelings. “We are both things that have been raised not from birth but from death,” she once said. “From an ending rather than a beginning, and we will exist together until we die again and the world dies with us.”

We’re apart now. Properly apart. And I feel I can finally start my life. But the burden of her loneliness feels like it’ll never leave me.” (pp. 102-103)

“I don’t know how other people do it. How do I go from where I am here, being moved out of photographs, and replaced with actresses like I don’t exist, to where I want to be? In just a couple of months, I’ll run out of money to rent my studio. How is it that vampires in all the books and films and TV programs always seem to be so successful and wealthy, and able to rent or even buy studios, flats, houses, sometimes whole estates? How is it that they all manage to feed themselves and stay so strong too – how can they all, including the good ones with souls, get hold of blood so easily, while I’ve struggled to even get some fresh pig blood—while I struggle, now, to even replace what I got from a meager duck?

I feel like giving up, lying down on this wall and closing my eyes and just doing nothing—not bothering to try to fit into the human world, not bothering to make friends and art, not bothering to source blood and feed myself. Maybe little plants and mushrooms would grow out of me, while I stayed just a little bit alive, and I’d become a beautiful thing, unconscious but living and giving life, in lots of different ways. I could be a bird or squirrel perch, or a piece of art that people could come and look at. I could just stay here, like a rock, in rain and sunshine, not changing, just be-ing, until someone came along and brought me food and fed me.” (pp. 153-154)

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Leave a Reply